Adam Meghji Is Changing the Way Art Is Bought and Sold with AI

Adam Meghji turned his love for computers into entrepreneurship: In university, he helped musicians sell MP3s to fans overseas using PayPal before iTunes dominated the market, and soon started his own online event ticketing platform. After selling that company to Ticketmaster in 2015, he switched gears and turned to art. Now, Meghji is focused on authenticating and selling pieces of contemporary artwork with his start-up, Peggy.

I grew up in Waterloo, Ont., a city known for its entrepreneurial and technical contributions. There must be something in the water, because that rubbed off on me. When I was seven years old, my dad brought home a big box with a computer inside. I remember the moment he placed it on the laundry room floor. Something sparked inside me and I became a lifelong tinkerer. At the age of 11, I was building dial-up communities—online communities that predated the modern internet where you could dial in to other people’s computers using a phone line and modem, and do things like write notes, transfer files and play games. I begged my dad for my own phone line so people could dial in and reach me. That’s how hardcore nerds like me connected before the internet.

I always had tons of ideas for online projects, and I couldn’t help trying to implement them—I knew how, because I taught myself to code. In an elementary school science fair, for example, I drew on my experience building online communities and built a web-based platform for medical professionals. I basically created a full e-health system where doctors could log in, upload and exchange patient information and interact with their patients. The science fair judges hated it. “A doctor will never put patient records into a computer,” they said. I was reprimanded for even thinking this was possible. If I had gotten better advice and turned that into a product, maybe I’d be a billionaire.

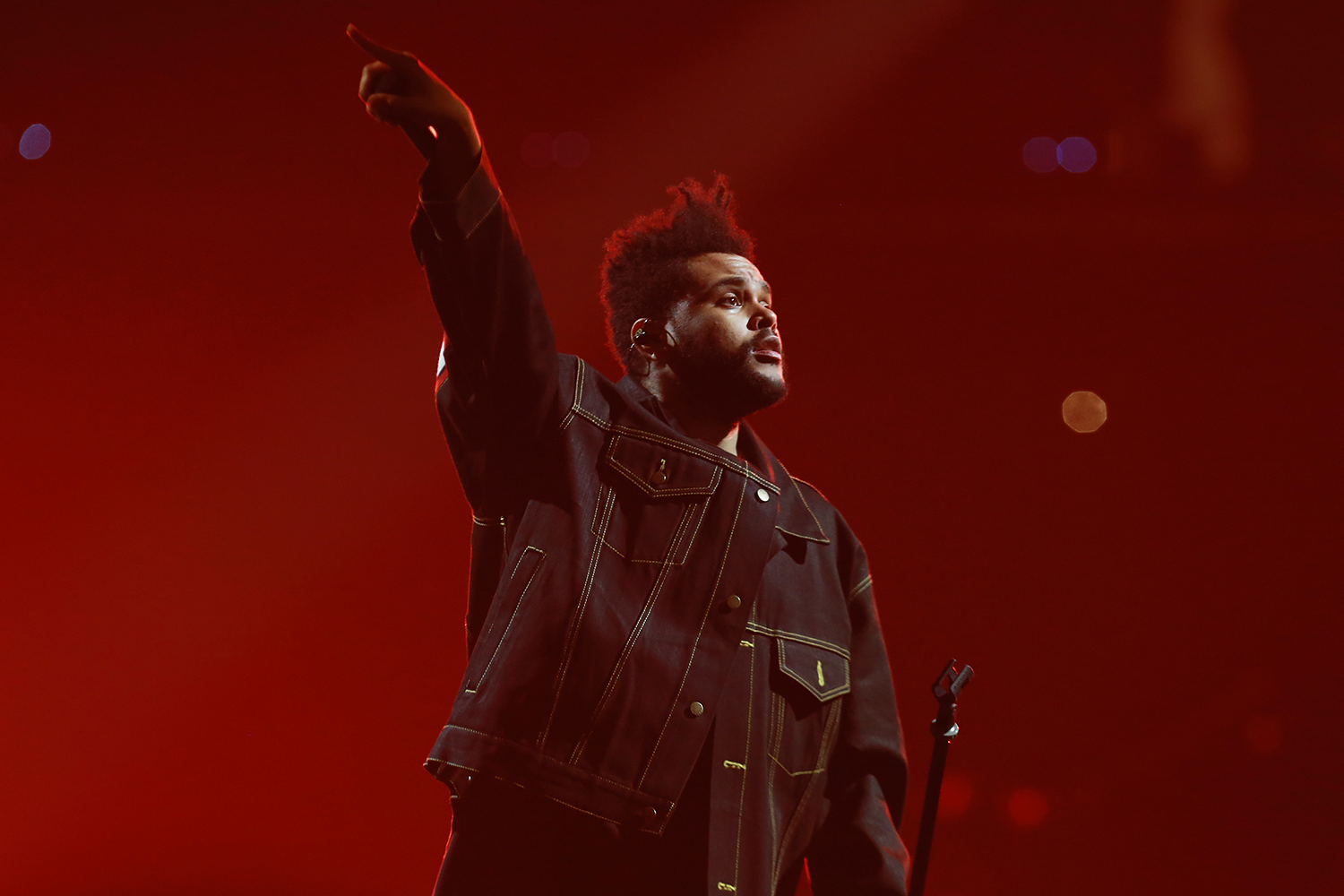

A couple of years later, I moved my dial-up communities onto the web. I kept the passion for computers and coding up throughout high school. In 2000, I went to the University of Guelph for computer science, but alongside my formal education, I was always building things. I’m also a DJ, and all my best friends were (and still are) musicians and creatives. I noticed that none of them had music available online. So I built a music platform to promote my friends. I walked them through getting on my platform, and sold MP3s to kids in Europe using PayPal well before iTunes became a thing.

RELATED: How Canada’s Crumbling Health Care System Opened the Door to For-profit Virtual Care

When I graduated, I started helping other Canadian companies like Metavera and Intellitactics as a lead developer, writing code and helping them develop products. All that time, I knew I wanted to start my own company. But I thought, “Who am I to tell a designer how to design, or a salesperson how to sell, before I get experience in different roles?” I looked for opportunities to be multidisciplinary, believing that one day, I would be responsible for managing team members like them. I worked at a company called Unata, for which I co-built a prototype that would form the basis of the Grocery Gateway app, which was later bought by Instacart. I spent some time building car-sharing technology and built the leading competition to Zipcar.

Around 2011, I realized I had enough experience and it was time to cross the chasm into becoming a founder. At the same time, I met Craig Follett on LinkedIn. He reached out to me in search of a technical co-founder, or lead developer, and something about him struck me as heartfelt and smart. I had been working on a food delivery idea, and Craig and I put our ideas together and founder-dated, so to speak. We spent six weeks getting to know each other and making sure we vibed well. On the same day in 2011, we both quit our jobs and launched Universe, a platform for event ticketing, and bought the domain universe.com.

“People were running their own websites and wanted to sell tickets directly within their own sites and apps, rather than linking out to another site”

We recognized that the world was shifting towards mobile. People were running their own websites and wanted to sell tickets directly within their own sites and apps, rather than linking out to another site. With one line of code, we built tech that would allow people to sell tickets that way. We were growing aggressively, but thought, “Why not leapfrog onto the shoulders of the industry giant?” And so, we were purchased by Ticketmaster in 2015.

I stayed on as Ticketmaster’s VP of technology and eventually became VP of cryptographic ticketing, which meant I was the “blockchain guy” and got to sit on the other side of the M&A table for the first time. From 2017 to 2019 when Ethereum smart contracts—basically contracts stored on a blockchain—became of interest, Live Nation tapped me to oversee the R&D of blockchain solutions for event ticketing. This culminated in me authoring a patent for blockchain ticketing. But it wasn’t long before I was ready to start another company.

My business partner Craig and I had been thinking about the art market for a while. In fact, the first thing he did after we sold our start-up to Ticketmaster was check out Art Basel in Switzerland. He absolutely loved it, but neither of us loved how historically opaque and exclusionary the art world was. Everyday people don’t have a straightforward way to participate in it—especially when it comes to investment and resale. Those pathways are obviously well-established for the ultra-wealthy. I had done research on blockchain and online marketplaces, and thought, “If I can use technology to sell event tickets, why can’t I do the same thing for a painting?”

RELATED: How Wattpad Co-founder Allen Lau Built a $750-Million Business

Auction houses are gatekeepers as authentication keeps people out of the art world. Picasso is dead, for instance, and there are a small number of experts who know his catalog and can authenticate the work. But the average artwork authenticator isn’t likely to be familiar with the work of lesser-known artists, so those artworks aren’t nearly as investable as something like a Picasso, because they can’t be authenticated in the same way.

Our hypothesis was that if we create an AI that can authenticate the work, we can create a thriving, accessible art marketplace. And so in 2020, Peggy was born. Using proprietary authentication tech, our platform unites collectors, artists and gallerists, focusing on museum-grade artwork that sells between US$500 and US$25,000. Through us, artists can safely sell their work to collectors. And since the artwork authentication remains in Peggy, if a collector decides to sell it to someone else, it can be authenticated directly on our platform.

“The average artwork authenticator isn’t likely to be familiar with the work of lesser-known artists”

Peggy is also in a unique position to enforce royalties for artists. Right now, artists get paid for every painting they sell, but don’t see a dime in resales—even when their work appreciates in value. In other words, artists typically don’t get royalties like musicians do. But because we have this long-term relationship with artists and manage the authentication, we can pay five per cent royalties on every repeat transaction, and we’re the only platform that can do that. In 10 years, I want to be able to look back and say we processed a billion dollars of secondary artist royalty payments that they would never have otherwise received.

By 2022, we’d raised $10.8 million in angel and seed round funding. Given the economic climate, I think our fundraising success shows that art is a stable asset class and investment. This year, we launched to the public via the App store (both iOS and Android). For now, we’re focusing on contemporary artists globally, specializing in paintings and original work on paper—no prints or photographs. My vision is that in the next five years, Peggy will become a household name, and the idea of investing in art from living, relevant artists who need your support will be second-nature.