Why Tickets for Upcoming Concerts Are So Pricey

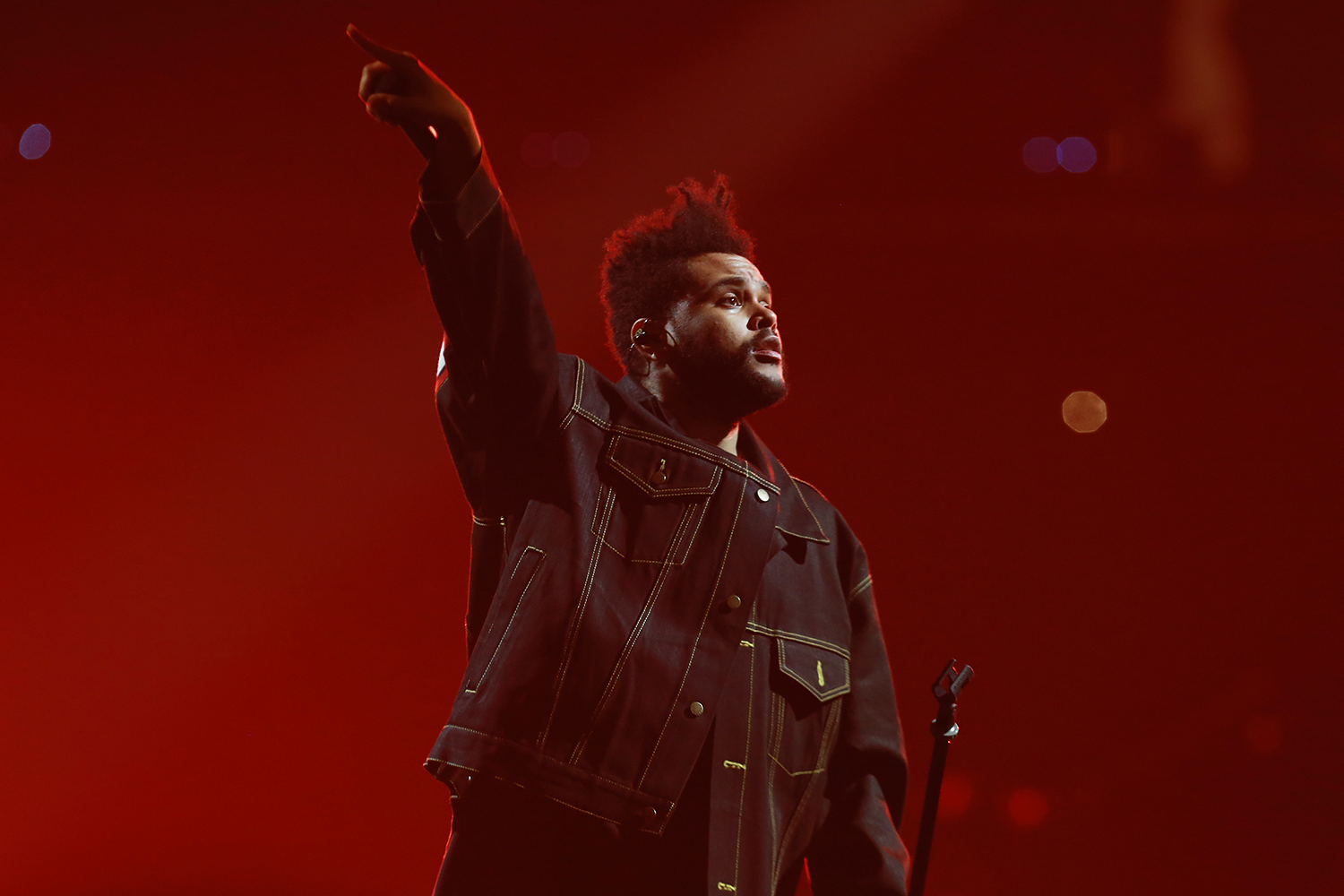

If you’ve been to a live show recently, chances are you were hit with sticker shock—and not just from $15 beer. As of late June, music fans paid an average of US$108 for a ticket to one of the 100 most popular tours, which include artists like Bad Bunny and Elton John, in North America—a nearly 18 per cent increase from 2019, according to data provider Pollstar. Resale tickets to see The Weeknd, who is performing in Toronto on September 22 after the Rogers outage forced him to reschedule his July show, range from $258 to more than $12,000 apiece.

Inflation, labour shortages and pent-up demand are all contributing to high prices. But while expensive concert tickets might seem like a recent problem, prices in North America have risen by more than 60 per cent since 2011—outpacing the rate of inflation. A large factor? The outsized control Ticketmaster has on the Canadian market—an issue experts say likely won’t change anytime soon.

Outrage over how Ticketmaster prices concert tickets

Ticketmaster has angered fans for years. More than a decade ago, the world’s biggest concert promoter, Live Nation, bought the California-based ticketing platform to create Live Nation Entertainment, a ticketing and live event promotion company. At the time, fans, artists, regulators and competitors aired concerns that merging the two businesses would affect concert prices.

Since then, many concerns have been validated. There have been allegations that Live Nation Entertainment asserts its control over the market by withholding tickets from venues that don’t choose Ticketmaster as their ticketing provider. When fans buy tickets on the site, they often complain of unusually high prices.

Most recently, fans blasted Ticketmaster for its incredibly expensive tickets for Bruce Springsteen’s North American tour. After waiting in a long digital queue, people were furious to find tickets listed at nearly US$5,000 due to Ticketmaster’s “dynamic pricing system,” which allows prices to fluctuate based on demand. (Ticketmaster responded by sharing data stating the average ticket price to see Springsteen was US$202 and just 1.3 per cent of fans paid more than $1,000.) Tickets to see Harry Styles at his sole Canadian stop in Toronto spiked from $200 to over $1,000 apiece within several hours of the tickets going on sale.

Since 2011, Ticketmaster has allowed promoters to adjust prices according to supply and demand through a dynamic pricing strategy—similar to hotels, airlines and rideshare services. When demand is high, prices tend to go up. “They don’t want all the tickets to sell out early because it means they could have sold them at a higher price,” says David Soberman, a professor of marketing at the Rotman School of Management. Ticketmaster argues that this pricing strategy helps artists pocket more profit from ticket sales.

Ticketmaster has faced several lawsuits over its tactics—including in Canada. In 2019, the Competition Bureau ordered Ticketmaster to pay $4.5 million to settle claims that its pricing strategy misled fans by advertising a lower price only to raise it by tacking on mandatory fees at checkout. Those charges can raise the price of a ticket from 20 per cent to 65 per cent.

Artists have also pushed back against the ticketing giant. In 1994, Pearl Jam tried to fight Ticketmaster and enforce a maximum US$1.80 service fee on tickets to their shows. Band members even testified before U.S. Congress, arguing that Ticketmaster broke antitrust laws and its monopoly on the market allowed it to charge exorbitant fees. The U.S. Justice Department opened an investigation, but concluded Ticketmaster was not breaking the law.

While concertgoers have placed blame on ticketing platforms, there’s also the issue of scalpers. Kenneth Wong, an associate professor of marketing at the Smith School of Business, says that about only 25 per cent of tickets to see a top artist are bought by the general public. “The rest are sold to brokers, scalpers, fan clubs and credit card agencies,” he says. This can be a problem because brokers and scalpers might use bots to scoop up tickets, which are then resold for much higher prices.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to get around bots. Pre-sale access—often the best route to snagging a ticket—requires fans to go the extra mile by buying merch or an album that comes with a pre-sale code. But because most of these codes are generic and often shared online, scalpers can beat fans to the race anyway.

Inflation is contributing to high concert ticket prices

Pent-up demand from the pandemic, inflation and labour shortages are adding fuel to the fire—and are adding costs that are being passed down to fans, says Wong. Tours are typically planned and budgeted around one year in advance. According to Pollstar, we’re starting to see today’s high cost of touring reflected in ticket prices.

It’s a tough situation for artists, who may need to tour to make money, but are faced with rising labour and production costs. As streaming platforms have become more popular, artists are increasingly turning to live shows for a bigger chunk of their earnings. Streaming platforms might only pay artists cents—or less than a cent—per stream, which means artists often end up making less than they would from a physical album sale.

The future of concert ticket prices

Wong explains that unless more ticketing platforms enter the market or the Competition Bureau steps in, prices for concert tickets will remain high. In 2017, lawmakers in Ontario did try to regulate prices for shows through the Ticket Sales Act by introducing a rule that would have capped resale prices at 50 per cent above their face value. But Ontario scrapped that in 2019, apparently because there was no way to actually enforce it.

For Canadians on the hunt for cheaper resale tickets, scouring apps like Gametime, Vivid Seats and Seat Geek might be worth a shot. Gametime guarantees that if a customer finds a cheaper ticket elsewhere, the app will add 110 per cent of the difference in the form of credits to their account. StubHub is another option, but the platform has caught flack for adding on additional fees at checkout.

Getting your hands on a reasonably priced concert ticket will test your patience, but it might be worth it. An analysis by financial advice site FinanceBuzz found that fans spent 33 per cent less than the average price if they bought a ticket on the day of a concert, and 27 per cent less if they purchased it the day before. So in the case of concert tickets, it pays to be late for the show.