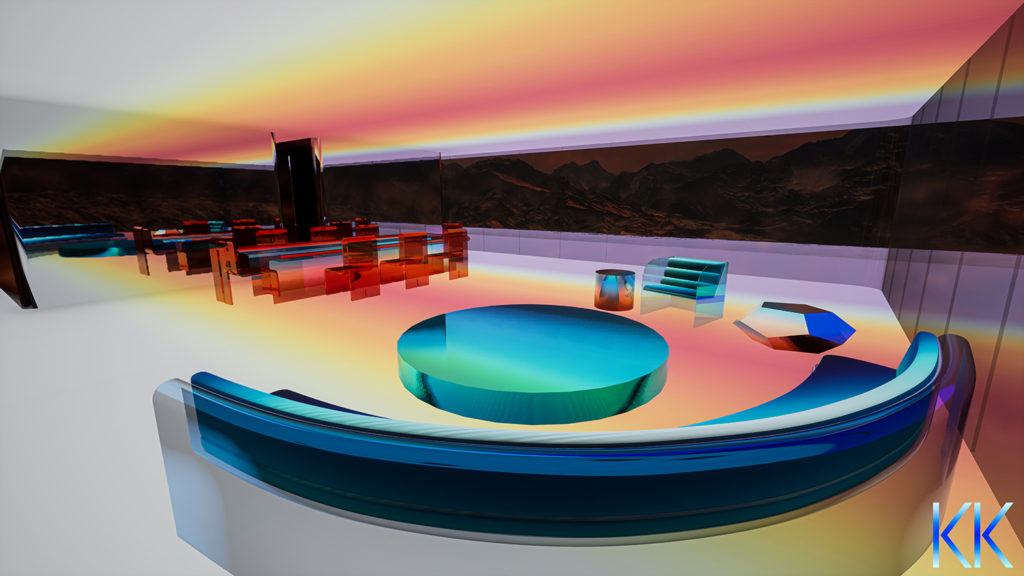

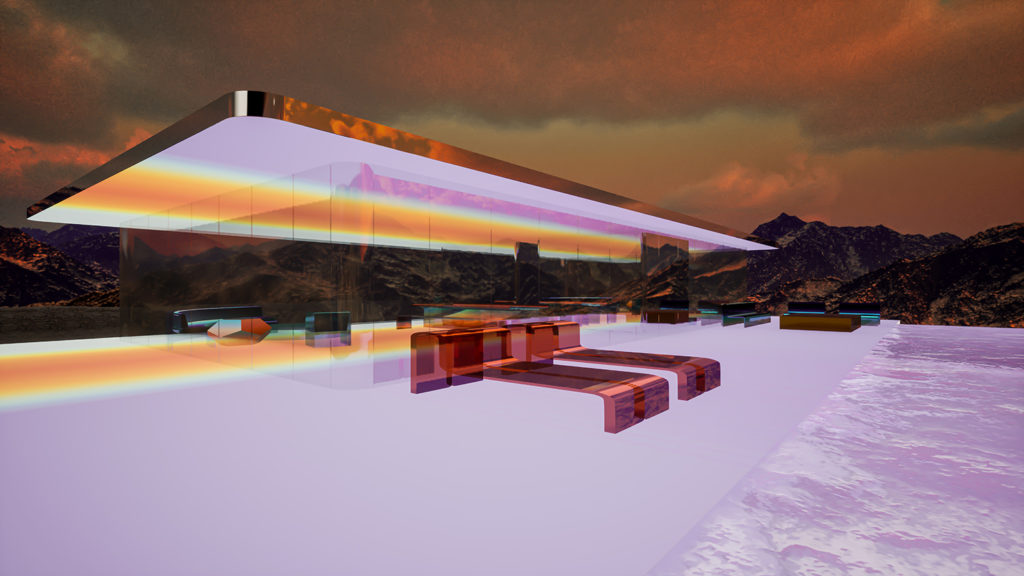

Krista Kim’s dream home didn’t exist, so she built it herself—in the metaverse. In 2020, cooped up with her two kids in a Toronto condo during the Covid lockdown, the digital artist began designing her perfect escape, leaving no detail overlooked. She sketched out a glassed-walled bungalow villa with rugged mountain views and a serene Zen-garden layout inspired by Japan, where she lived for three years in the mid-2000s. There was an infinity pool, a walk-in closet and a tightly curated selection of light-bouncing translucent furniture. Curiously, Kim’s plan didn’t include a kitchen. An odd choice, but Mars House, as she called it, wasn’t made for everyone. “I imagined creating a house that would heal me,” she says. She also hoped she’d find a buyer. “The question was: Would anyone else understand what I was selling?”

As it turns out, someone did. Kim’s futuristic dreamscape sold for approximately US$512,000 in March of 2021. The metaverse is a loosely but increasingly understood shared virtual space, accessible via smartphone, goggles or headset—and it’s the newest frontier in the global real estate blitz. The sale of Mars House, a 3-D file rendered using the video game software Unreal Engine, marked the metaverse’s first-ever NFT-based residential transaction.

For individual users, metaverse property might function similarly to a hyper-modern Myspace—a place to “host” friends, co-work, play games and display their avatar’s fully stocked wardrobe. For brands and influencers clamouring for ever more consumer eyeballs, virtual land holdings offer a whole new world of ways to reach them. According to data from analytics firm MetaMetric Solutions, real estate sales in the metaverse are expected to reach $1 billion this year, due in large part to a recent deluge of commercial operations hanging out their virtual shingles. Gucci, Samsung, Atari, Nike, PwC and other marquee brands have already snapped up plots of metaverse land for development; Warner Music Group has announced plans to build a concert stage; and last December, one of Snoop Dogg’s most ardent fans dropped US$450,000 for a plot next to the rapper’s mansion in The Sandbox, a popular gaming platform. In June of 2021, Krista Kim’s Mars House was rented out for a wedding, which is itself part of a growing industry. Several couples have recently tied the knot in metaverse chapels. They designed their venues with architects; partied with avatars of friends, families and metaverse strangers; and even exchanged NFT art in lieu of rings. As users become more comfortable socializing, shopping, visiting restaurants, gaming and working within a digital analog to the real world, brands and developers will be there waiting for them.

Until recently, the metaverse was—even as a concept—entirely too arcane for the average internet user. The term made its first appearance in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 sci-fi novel, Snow Crash, which foretold the existence of a hyperconnected immersive world not unlike the internet. In Web 3.0, the internet’s new decentralized iteration, users—not corporate monopolies—have control. It’s a world human beings are building together, and it’ll exist even after we unplug.

Users (and their avatars) have bopped around virtual gaming platforms like Roblox and Second Life for almost two decades. What’s different now is our level of technological sophistication, the option to buy “real” digital property and the unified corporate thrust to make it all catch on. The most notable effort is Facebook’s 2021 rebrand to Meta Platforms, Inc., which unambiguously signalled its intent to lead the charge into our brave new three-dimensional world. Last September, the company unveiled its first set of smart glasses, Ray-Ban Stories, which allow wearers to take calls and film videos and, in the future, will likely be able to superimpose a virtual overlay onto their day-to-day activities. They join the less sleek Oculus VR headset in the brand’s growing suite of augmented-reality gadgets.

Like terrestrial homebuyers, users keen to buy or sell real estate in the metaverse will have to go through a rigmarole not unlike the one for bricks and mortar. Right now, land sales in the metaverse are typically concentrated within the “Big Four” platforms—Decentraland, The Sandbox, Somnium Space and Cryptovoxels—which are developed and owned by users. (To date, their combined total of virtual plots is just under 300,000.) You can buy your plot using the cryptocurrency that’s native to each platform—The Sandbox, for example, uses $SAND, which you can buy on the Ethereum blockchain. In addition to the Big Four platforms, third-party sites like Opensea.io and Nonfungible.com allow sellers to advertise property listings in the vein of Zillow and even broker negotiations. Instead of a title deed, ownership is conferred via non-fungible tokens, or NFTs— another virtual gold rush—which are essentially proof-of-purchase certificates stored on the blockchain. Mars House sold for 288 Ether via the art marketplace SuperRare. Kim owns the copyright, but the buyer, an enterprising user simply known as @artontheinternet, owns the asset itself.

Each plot of metaverse land is made up of pixels; the average measurements depend on the platform used. Decentraland and Somnium Space have their own suite of builders at the ready to help new users, but you can just as easily find pre-constructed homes in online marketplaces. In The Sandbox, parcels have a blocky, almost Legoesque aesthetic. Decentraland’s pop-art look, on the other hand, aligns nicely with the platform’s art, concert and film utilities.

Outside of the metaverse, some people are mystified by those who invest thousands of real dollars in pixels they can never technically visit. But it’s not the size of the lot that matters—it’s what owners do with it. The true value of each space is predicated on how the buyer programs their holdings. Some, for instance, might choose to rent their plot, like an abstract Airbnb, to earn crypto tokens on the platform. And for brands, the revenue possibilities are almost endless: Many use the land as advertising and event space. As the technology develops, others will set up storefronts to hawk loads of products to a whole new digital customer base. It might be the most brilliant community-building exercise we’ve seen in recent history—or, at least, that’s the hope.

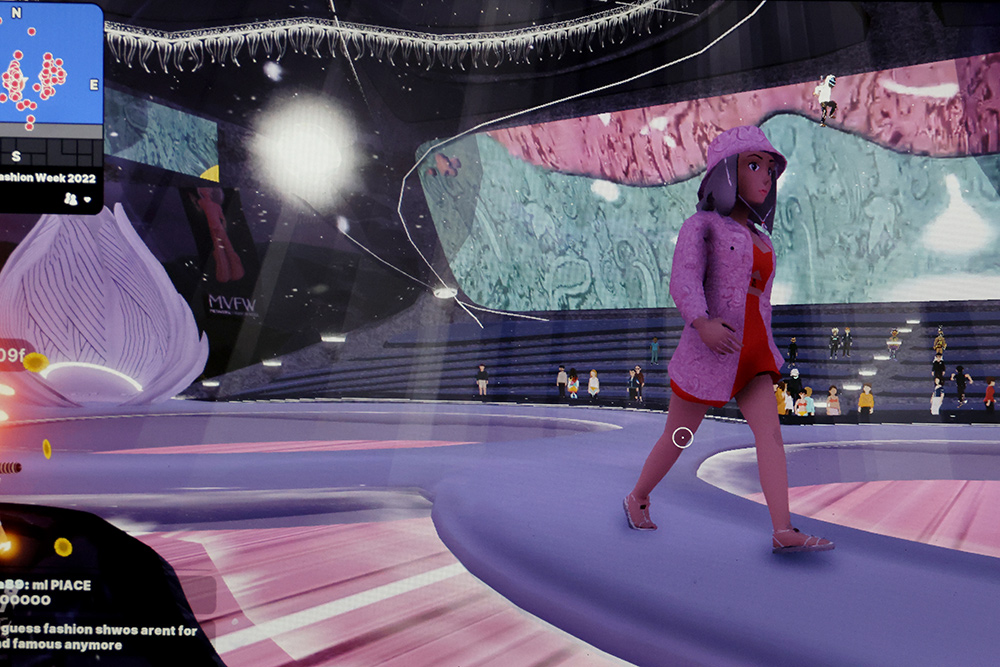

Even in the metaverse, location is everything. In Decentraland, neighbourhoods are designated for specific activities; for example, there’s Festival Land (for live music events), University (for education) and District X (for clandestine dating adventures and adult-themed e-stores). Its fashion district is of particular interest to the Metaverse Group, a Toronto-based virtual-real-estate company that scooped up more than 100 of the area’s 16-by-16-metre parcels for US$2.4 million last November. In March, the group hosted the very first Metaverse Fashion Week, in Decentraland—which has more than 500,000 monthly users who have spent more than US$20 million on the platform to date. It featured after-parties, panels and runway shows featuring virtual clothing from real-life luxury houses. Brands like Tommy Hilfiger, Mugler and the fast-fashion chain Cider paid a premium to secure billboards close to the event’s main drag. (German designer Philipp Plein went the lone-wolf route, showing his own collection off-runway at his $1.4-million Decentraland estate.)

For Lorne Sugarman, Metaverse Group’s CEO, the excitement is warranted, if familiar. Before he joined the firm’s executive suite in 2021, Sugarman was a long-time investment banker who had a ringside seat to the original dotcom boom. “When I looked at the metaverse, I said, ‘Wow, this is what I saw back in the 1990s,’” he says. “We’re creating, to some degree, the Facebook or Google of metaverse real estate. If you ask people whether they wished they’d bought with those companies 10 years ago, they would say ‘Of course.’ So, yes, we’re early, but I really believe this is just the next iteration of the internet.”

The Metaverse Group’s co-founders, Michael Gord and Jason Cassidy, presciently accumulated virtual plots for their portfolio as far back as 2018. Their largest holdings are in Decentraland, close to Genesis Plaza. That’s the spawning area—an entry point for avatars. To this day, they’re always trying to figure out where those high-traffic areas are.

Sugarman compares his company to a kind of virtual Brookfield Properties. Just like a developer, Metaverse Group buys, leases and rents commercial space to tenants—or, in this case, avatars of tenants. One of its most ambitious developments to date is Decentraland’s Tokens.com Tower, which contains stores, businesses and even a news channel. Where Brookfield and Metaverse Group diverge is their level of investment in a given brand’s success: Sugarman’s team includes virtual designers and software developers tasked with helping tenants shape the look and feel of their properties. Occasionally, they advise clients on how best to sell cutting-edge wearables or other digital goods. Many of these tenant companies don’t have a deep understanding of the metaverse, which is where Sugarman and his colleagues come in—as paid consultants.

The key to profitability in real estate is scarcity, or the illusion thereof, which is much easier to achieve with tangible, IRL properties. And yet, so far, that tried-and-true sales technique has translated seamlessly to the metaverse. In December of 2017, plots in Decentraland were going for US$20. In 2021, around the time that many users clocked the platform’s cachet, they were selling at an average price of US$6,000. Even the mere insinuation of prestige can cause a parcel’s price to spike: The virtual-real-estate company Republic Realm recently dropped US$4.3 million on plots intended to house “Fantasy Islands,” a collection of luxury villas in The Sandbox. The prevailing wisdom seems to be that if buyers get in early enough in prime spaces, they will be able to sell their properties at a premium later on. Of course, there are few guarantees in worlds that are still being built.

Start-ups like MetaVRse, a Canadian VR-product-development company based in Toronto, are trying to define some parameters for the metaverse. This is crucial for preventing the industry from becoming a virtual Wild West. “Skeptics will say ‘Well, the metaverse is infinite. Why are you putting confines on it?’” says MetaVRse co-founder Alan Smithson. “But if I say to clients ‘Just build whatever and wherever you want, and just go nuts,’ they won’t know where to go. We’re also not a get-rich-quick scheme. We’re interested in long-term value creation. It took us years to build the infrastructure for this.”

MetaVRse’s most ambitious project, launching this year, is TheMall, a 3-D shopping centre located at TheMall.io. The complex houses 100 “floors,” which each measure one million metaverse square feet. It costs between $1 and $10 per square foot to build. (Smithson says it’s the metaverse equivalent of the Dubai Mall but multiplied by eight.) At first glance, TheMall scans like a virtual Hudson’s Bay, with dedicated spaces for womenswear, menswear, sporting goods and electronics. Then, in true virtual-reality fashion, there’s a welcome floor—where visitors build their avatars—plus floors for mini-games, live events, a museum and a full-service casino dealing in crypto and fiat currency. Eventually, Smithson says, items bought in TheMall will be shippable to addresses in the real world. So far, the business model has proved attractive: Each floor is sold as an NFT at a starting price of roughly US$300,000, and 31 are already spoken for. “If you asked me a year and a half ago whether somebody would pay real money for virtual land, I would have said ‘You’re insane,’” Smithson says. “But we thought: If this is going to work, it can’t just be like a Ponzi scheme where I buy a real estate asset, sell it to you and then you sell it and it’s all held up with nothing.” MetaVRse’s staffers are vetting anyone who wants to buy a floor of The Mall. They’re curating the entire ecosytem. “We want people to have experiences that make it worthwhile to stay.”

It’ll also be worthwhile for those on the so-called building side of things. Experts at EY Switzerland recently predicted a construction boom in the space, which will likely draw participation from real-life tradespeople, building-modelling experts and even professional architects. The MetaVRse team has grown from around 11 to almost 40 in the span of a year. Sales and marketing is one chunk of it, but the real boom, Smithson says, is in the creator sphere: coders, 3-D modellers, developers and, of course, avatar designers.

Being able to conjure a virtual world into existence—and then sell products in it—is a huge testament to the vision of Web 3.0 creators and our collective commitment to buying things, well, anywhere we can. There are tangible reasons for brands to be in the metaverse, says Alfred Lehar, associate professor of finance at the University of Calgary’s Haskayne School of Business. “If it’s done well,” he says, “it offers new opportunities for companies to interact with customers, a competitive edge and advertising value, all of which hopefully translate into sales in the real world. There are legitimate business reasons to be there—but there are also a lot of risks.”

Among them is the fact that in a made-up universe with made-up properties, the few rules that do exist are uniquely vulnerable to the whims of the marketplace. Lehar warns that buyers could always go to a different platform, and no one really knows how long any of these shifting universes will stick around. Even if some emerge as the most popular ones today, they might not be popular five years from now. “Then you have some real estate that turns out to be pretty worthless,” he says.

A key conundrum is that if virtual real estate can technically be created in infinite amounts, who is to say it won’t be? In the case of Decentraland, at least, there’s the Decentralized Autonomous Organization, or DAO, which is a governing body of stakeholders that controls the number of parcels available on the platform. Adding plots ad infinitum would decrease the value of the virtual land and its currency, so the DOA’s job is to prevent that from happening. In many ways, the metaverse’s key selling point—freedom—could prove to be its biggest limitation. There’s the issue of regulatory ambiguity: International governments are still catching up to how metaversalreal- estate transactions should be regulated—with value-added tax or capital gains?

Lehar also warns of the kinds of illegal activity that could proliferate without proper oversight: bad deals, insider trading, bots that buy land and then resell it at exorbitant prices. As recently as May, several American plot owners fell victim to a phishing scheme and had their user credentials stolen. Within days, their land was gone. “These things are happening in the metaverse that don’t happen in real-world real estate because they’re outlawed,” Lehar says.

For Mars House creator Krista Kim, one of the most dystopian developments would be if the metaverse became simply a container for ad space. Her augmented-reality healing home is one part of her broader manifesto: to explore how technology can be used as a tool for well-being. “I had so many people reach out to me, like, ‘Let’s build houses together and sell them.’ And I was like, ‘No, this is not my interest,’” Kim says. “The way to create a viable real estate market in the metaverse is to focus on community—making immersive cultural meeting places—on top of the spaces themselves.” So far, Kim’s plans include creating healing installations, like meditation and yoga sessions, but every so often, she dips outside of the metaverse: She recently designed a real-life psychedelic trunk for Louis Vuitton’s 200th anniversary, and she’s planning to create a one-of-a-kind physical furniture line inspired by the pieces in Mars House.

As for how the metaverse will expand, there are, as always, more guesses than answers. A market research report from BrandEssence projects that its real-estate sector will grow at a compound annual rate of 31 per cent through 2028. In preparation for our mixed-reality future, Kim bought her first Oculus headset after the sale of Mars House. In April, Decentraland’s average daily number of sales transactions slumped to 28.6, which signalled to analysts that buyers hadn’t lost their taste for property but were simply keen to hang onto the ones they already had. “Every asset class—whether it’s gold, oil or metaverse real estate—is probably going to have bubbles,” Sugarman says. “It’s no different than Toronto real estate. So if you’re thinking of investing, you need to look at certain criteria: Is it the right time? What are the comparable prices? Does this purchase make sense? And who are my neighbours?”

Recently, the Metaverse Group signed Forever21 as a client for an immersive virtual storefront. The commercial side of things is certainly flourishing, but Sugarman predicts an oncoming boom that will be very reminiscent of our shared, non-virtual reality: People are starting to build condos in the metaverse.