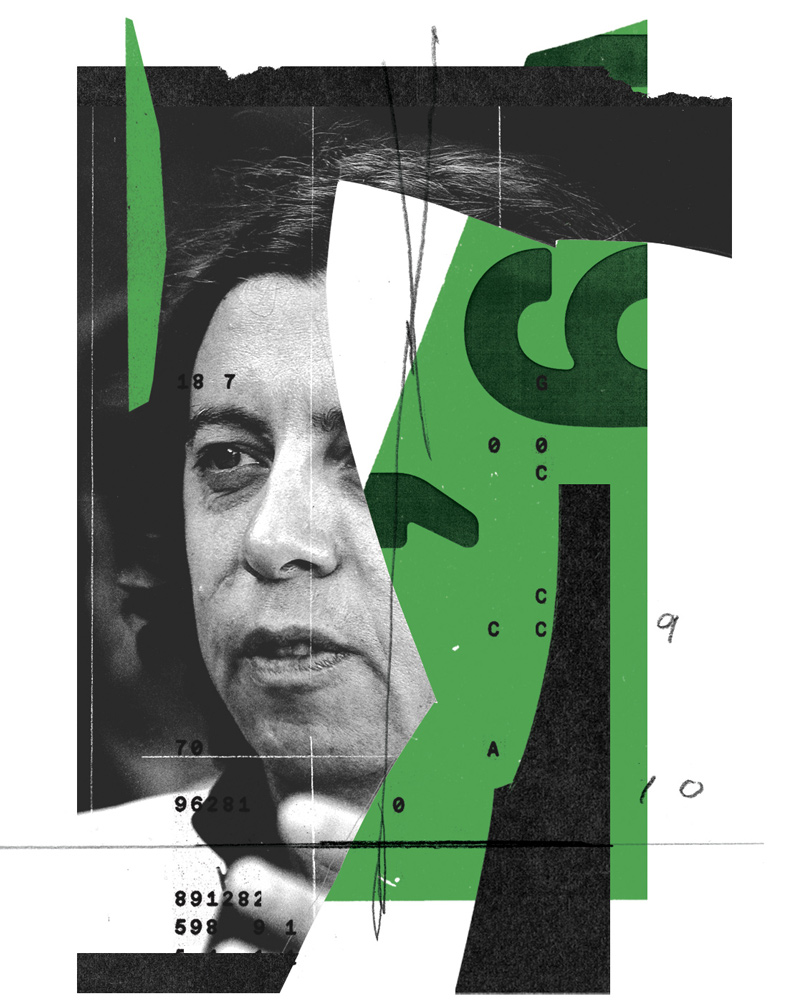

When they started out in the ’90s, David Sharpe and Natasha Hilfer were both both fiercely smart and exceedingly ambitious, with eyes on the finance sector. But both believed they had to overcome, as David once said, the implicit need-not-apply sign Bay Street hung to ward off anyone who was different. Natasha, who holds an MBA from the Rotman School of Management, had to battle the old boys’ club. David, meanwhile, who is Mohawk and a member of the Tyendinaga First Nation, felt he had to hide the fact that he is Indigenous. He would repeatedly say that, for the first 15 years of his career, he refused to acknowledge his roots to anybody he worked with: “Because,” as he put it, “I wanted to grab power.”

The pair married in 1996 and soon made it on Bay Street. David graduated from Queen’s University with a law degree, got his Master of Laws at Osgoode Hall and then earned his MBA from Ivey Business School. From there, he worked as the chief compliance officer at several firms, including Citigroup and CI Financial, and served as director of investigations at the Mutual Fund Dealers Association. Natasha Sharpe earned a sparkling reputation as a risk expert at the Bank of Montreal. After the devastating 2008 recession, Sun Life Financial wooed her into becoming its first-ever chief credit risk officer; she was in charge of creating the company’s risk policy for its $110 billion in managed assets.

After only two years at Sun Life, Natasha left to start her own company in 2012, securing financing from a friend, Jenny Coco. Natasha believed her new firm could address a gap in the post-recession lending market, doling out loans to Canadian companies that couldn’t secure the necessary cash to do things like buy inventory, meet capital expenditures or restructure debt. She named the company Bridging Finance, a nod to its role as a figurative bridge, and soon hitched her professional star to her husband’s, hiring him as the COO.

Over the next decade, the Sharpes turned Bridging into a Bay Street darling. Every major bank and independent brokerage in the country made its private debt fund eligible for sale. Bridging specialized in two types of lending strategies: factoring and asset-based. The first involved buying accounts receivables from mom-and-pop shops in need of a quick cash infusion. Take, for example, a jeweller that landed a big contract with a national retail chain—a good thing, except it would suddenly need to finance increased production. Bridging would buy the jeweller’s accounts receivable at a discount, then collect in full when the retailer paid Bridging. Asset-based lending, on the other hand, involved loaning money to less established companies, charging sky-high interest rates and ruthlessly collecting collateral if things went wrong. With purported annual returns of between seven and nine per cent by 2014, the Sharpes appeared to have conquered risk itself.

In 2016, David and Natasha shuffled positions; he became CEO, and she focused on her role as chief investment officer. By early 2020, Bridging had some 20,000 investors and $1.6 billion in assets under management. But few suspected that the Sharpes’ glittering, feel-good empire might have been built on lies. Today, the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) has implicated Bridging in a vast and complicated web of alleged misappropriation and fraud, and the Sharpes are at the centre of an unprecedented months-long hearing in front of the Capital Markets Tribunal. If the OSC’s case against them succeeds, the pair will be remembered as the joint architects of one of the most audacious frauds in Canadian history.

A couple of years before David was promoted to CEO of Bridging, he met a Winnipeg finance guy named Sean McCoshen. The two men quickly became close business allies. The way McCoshen told it, he was an investment banker who’d spent three years working in Dubai with a multinational private-equity firm to build a billion-dollar grain terminal. He claimed the project required extensive consultation with local Bedouin tribes, because it infringed on their traditional land. When he got back to Canada, he started a company, The Usand Group, to help First Nations secure financing for housing and other infrastructure projects. His purported mission no doubt appealed to David, who soon sunk millions of Bridging dollars into McCoshen’s projects.

In 2017, Bridging made a $30-million loan to Peguis First Nation, an Indigenous community of about 10,000 people in Manitoba, about 190 kilometres north of Winnipeg. McCoshen, who had a pre-existing business relationship with Peguis, helped broker the deal, telling David that the community needed money to address a housing shortage and lack of job opportunities. (Unlike David, Sean McCoshen has no Indigenous ancestry.) The problem was, the Bridging loan breached the conditions of the Bank of Montreal financing McCoshen had previously secured for the community, triggering an immediate demand for repayment. Peguis was forced to secure a second $30-million Bridging loan to pay BMO, and McCoshen earned $7.2 million from Peguis for facilitating the deals. By early 2022, Peguis was more than $140 million in the hole. As Peguis continued to fall behind, Bridging’s punishing interest rates only tunnelled the community further into debt.

Related: VC Funds Are Dominated by Men. These Women-Led Firms Are Trying to Change That

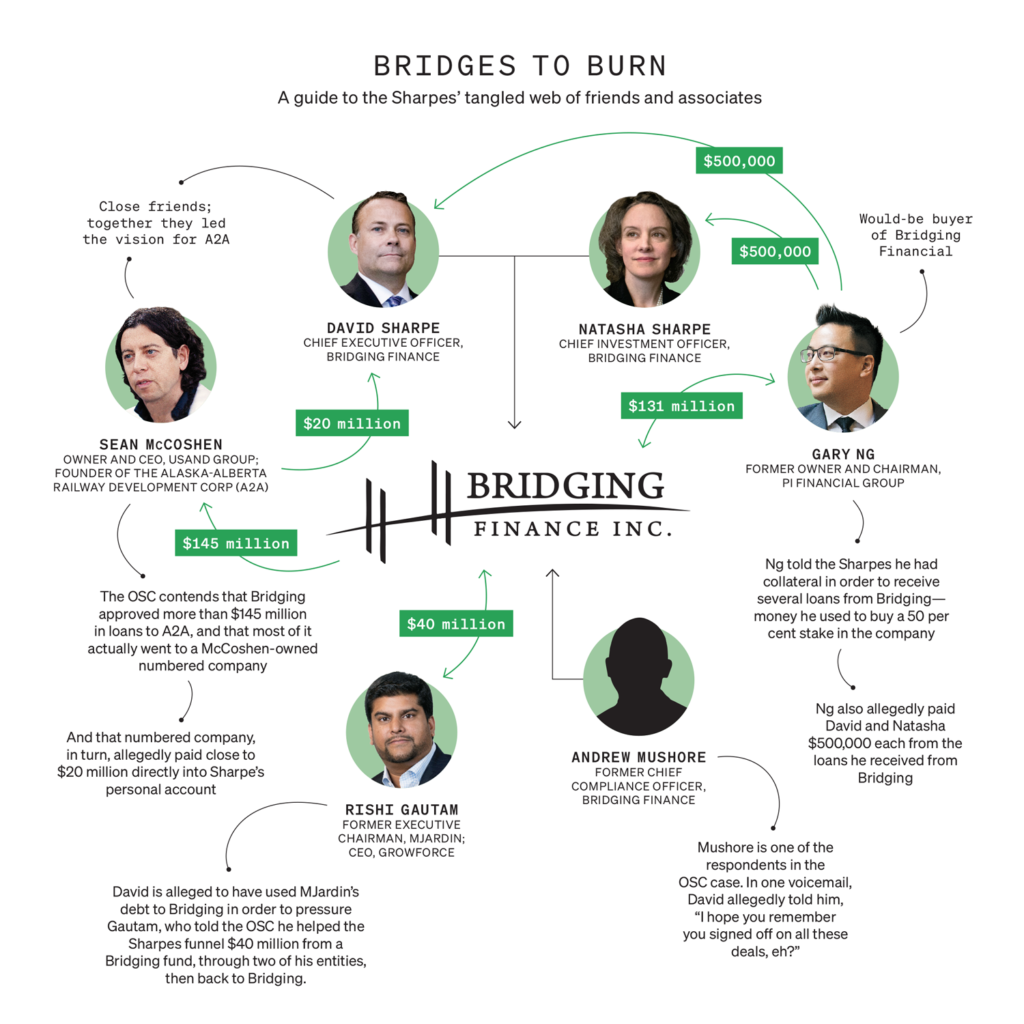

None of this stopped David Sharpe and McCoshen from partnering on an even bigger venture: an ambitious Alberta-to-Alaska railway project often called A2A. McCoshen’s crown jewel, the railway was meant to connect Fort McMurray to ports in Alaska, opening up Alberta oil to the global market while also allowing Indigenous communities to rake in cash through a 49 per cent ownership stake. Over six years, A2A borrowed at least $145 million from Bridging. Somewhere along the way, McCoshen started describing David as the project’s co-founder, and, in time, Bridging secured a $109-million equity stake in the railway’s parent company. The two friends even travelled together in 2019 to pitch the $22-billion project to Mike Pence, successfully obtaining the necessary permits from U.S. officials. One paper in Alaska speculated that McCoshen was the region’s saviour.

As David grew more powerful on Bay Street, he began embracing his Indigenous heritage and giving back to the community. In 2017, he donated $50,000 to Queen’s University so his alma mater could start the David Sharpe Indigenous Law Student Award. The next year, he donated another $100,000 toward a new bursary, followed by $250,000 for the school to start an Indigenous Knowledge Initiative. He joined the board of trustees at Queen’s, became an ambassador for Queen’s Law, taught an Indigenous law class and sat as the chair of the First Nations University of Canada. Several people who worked with David at that time described him as wonderful, freely sharing his expertise and genuinely invested in helping other Indigenous people succeed. As one former board member put it, “He was the whole package: He had the success, financially and reputation-wise, and the movie-star good looks.”

David’s public generosity, and the doors it opened, legitimized his status on Bay Street—and coincided with Bridging hitting $1 billion in assets under management. David celebrated at a bar decorated with giant gold balloons that spelled out “$1BN.” In 2020, the Association of Fundraising Professionals dubbed him one of its outstanding philanthropists of the year. Upon hearing the news, a professor at Queen’s gushed that David was simply the type of person who opened his chequebook and got stuff done.

But not all was well with McCoshen. Despite his stylings as a financial wizard, his past included a history of flirting the disaster line with his own personal finances and a series of accusations of receiving financial kickbacks. In 2016, APTN reported accusations against his firm, The Usand Group, by two First Nations chiefs who said that senior execs at the company had offered them money to hire Usand in order to secure loans for their communities. In exchange for both kickbacks and the loans, Usand charged exorbitant fees. At allegedly the time, Usand had already arranged about $113 million of financing with First Nations groups; it was aiming to triple that number. (McCoshen did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

David’s public generosity, and the doors it opened, legitimized his status on Bay Street—and coincided with Bridging hitting $1 billion in assets under management

If the Sharpes saw warning signs, they ignored them. Instead, it appears, they saw opportunity. With McCoshen by their side, their success only seemed to grow. But in reality, the OSC alleges, much of Bridging’s triumph was a ruse. In the fall 2018, for example, Bridging announced that it had bought out one of its partners, Ninepoint Financial, which had, until then, co-owned and co-managed one of Bridging’s investment funds. The OSC suggests that Bridging wanted out of the partnership because Ninepoint executives had started to suspect something was fishy about the money moving in and out of the fund. To pull off the purchase, David allegedly pressured Rishi Gautam, the head of MJardin, a cannabis company that owed Bridging $80 million, into a “back-to-back loan.” Gautam later told OSC investigators he agreed because he felt he wasn’t in a position to say no. And so, the Sharpes allegedly misappropriated roughly $40 million from a Bridging fund and loaned it to one of Gautam’s entities, River City Investments. In turn, a second Gautam-controlled entity, 3319891 Nova Scotia, loaned it back to Bridging. Then, the OSC says, they obscured the loan’s true origins and celebrated what they called a “great milestone.”

Bay Street’s conservative reputation is etched in buttoned-up grey suits. But, for all its calculation and strategy, the high-stakes financial world also thrives on theatre. It is full of big, schmoozy personalities, many of them living embodiments of fake it ’til you make it. A good salesperson needs a certain alchemy of bluster, charm and guts. CEOs gain reputations, allies and fortunes by marketing themselves as much as their company’s products or services. Confidence is expected; cockiness is welcome.

In 2019, the Sharpes became acquainted with Gary Ng, a young upstart who, like them, was familiar with Bay Street’s culture of brash ostentation. But neither of the Sharpes had anything on Ng’s ability to put on a show. Ng’s reputation prospered on self-mythologizing: that he was, as one publication later dubbed him, a financial “whiz kid” and—as he put it himself—Bay Street’s “succession plan.” As Ng would confidently say more than once, to media and on his own website, chaos breeds opportunity. He was certainly adept at creating both.

When Ng burst onto the scene in 2018, he had his story ready. He told people that he’d become an “internet millionaire” at age 16 and that he took that money and put it into a glass factory in China, which he sold for a $150-million profit. Then, he says, he mastered golf. Somewhere in his spare time, he says, he also served in the military. By 2008, he was a futures trader in Winnipeg, his hometown, and, according to him, quickly became the firm’s best. Next, at age 28, he acquired a small Toronto brokerage and renamed it Chippingham Financial Group. Then, at age 34, he bought PI Financial, one of Canada’s biggest investment firms, in an all-cash $100-million purchase. In one interview, he bragged, “I’ve been told I’m the most powerful man on Bay Street now that nobody’s ever heard of.”

Related: How a Government Worker Extorted Millions From Canadian Businesses

As his profile grew, Ng called himself an “admiral” who was working to amass a fleet of independent firms. He wanted ones focused on equity, trading, wealth management and, fortuitously for the Sharpes, debt. In 2019, he told the media that he wanted to increase his assets to $50 billion in just three years. “Given his track record,” wrote a BNN Bloomberg journalist, “you wouldn’t want to doubt him.” Yet Ng’s track record invited doubt. Chippingham was, in truth, fighting insolvency and mired in legal battles. The Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC) approved the PI transaction, in part because it hoped that by forcing PI to inherit Chippingham’s clients, it could save the firm from disaster. Ng wasn’t a financial whiz kid; he was struggling to keep his fleet afloat. Still, he wanted to buy Bridging, and he was prepared to pay $50 million to acquire a 50 per cent, non-controlling stake in it. Or, rather, he seemed prepared to pretend he would shell out the cash.

It’s unclear if the Sharpes knew the extent of his alleged lies—they later claimed to be shocked by the subterfuge. Either way, the couple appears to have helped facilitate at least some of Ng’s fantasy dealings. Here’s what the OSC says happened. After Ng expressed interest in purchasing Bridging, it loaned his companies about $50 million from its investor funds—money Ng then used, in part, to fund the acquisition. After the deal was signed, Bridging loaned him another $32 million in June 2019. Then, the OSC says, a month later, Ng begged the Sharpes to immediately “upsize” his loan with another $35 million, which they did. They gave one of his companies another $2 million in October, and, shortly after, they each received $500,000 from Ng. Another $10 million went to Ng’s companies in February 2020. All potential loans from Bridging’s funds were meant to be approved by an eight-member credit committee—of which the Sharpes were a part—but the OSC says that the Sharpes fudged certain details or outright concealed many of Bridging’s shady loans, such as those given to Ng. As a guarantee against all of this, Ng told David and Natasha that he had an investment account worth approximately $90 million. It didn’t exist.

In the end, PI’s general counsel, Richard Thomas, realized something was amiss and alerted the IIROC to his suspicions that Ng had reported a false investment account. Soon, Ng’s carefully crafted image began to unspool. The IIROC’s investigation concluded that Ng, along with one of his colleagues, had procured $172 million in loans, all on the basis of falsified collateral records. The organiation says he’d create brand new accounts and then grossly falsify their balances: He said one had a market value of more than $20.6 million and another more than $90 million when, in reality, they had a balance of $0 and $4, respectively. In other cases, says IIROC, he took existing accounts—belonging to his clients—and altered the documents to make it look like the accounts belonged to him. Altogether, he created millions in fictitious assets. (He did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

As a guarantee against all of this, Ng told David and Natasha that he had an investment account worth approximately $90 million. It didn’t exist.

David and Natasha caught wind of the accusations against Ng in early 2020 and confronted him, secretly recording the conversation. They say he admitted to it all. By the time the story broke, they seemed to have distanced themselves from Ng. Earlier media reports presented Bridging as just another firm Ng had fooled, a role the Sharpes appeared eager to play. At the same time, they must have feared that regulators would look too closely at their own books—and learn that Ng wasn’t a grievous mistake but rather one part of a pattern of apparent below-board dealings that seemed to extend far beyond him.

Long before the investigation into the Sharpes’ former business partner was announced, a financial consultant living in Montreal named Alejandro Cardot began to suspect Canada’s private debt industry was a sham. One of his relatives had asked him for advice on whether to invest in private debt funds. Unsure, Cardot dug around for information, eventually discovering Bridging. There was plenty about the company, he thought, that didn’t add up. To Cardot, Bridging’s claims of steady, constant returns didn’t make sense: It specialized in loaning money to companies that were too unstable to secure cash from the banks. Some of those loans, he figured were bound to go wrong and negatively affect Bridging.

Related: Scammers Are Posing as Recruiters on LinkedIn and Swindling Job Seekers

In time, Cardot found exactly what he expected: Many of the companies Bridging had granted millions to had gone spectacularly belly-up. Hygea, which described itself as a health-care holding company, owed Bridging more than US$122.5 million by the time it went bankrupt in early 2020; it represented at least 15 per cent of Bridging’s assets. Yet, Bridging didn’t write off the loss, nor did its returns seem to be affected at all. Cardot discovered repeated instances of companies being unable to pay back millions in Bridging loans. He was shocked that nobody else seemed to have caught on—that, in fact, Bridging was celebrated. He gathered all his research into one document and filed a whistle-blower report with the OSC. In it, he warned: “The pressure to keep making the numbers and monthly distributions will push Bridging to even more deceit. Until one morning we will wake up and the house of cards will have fallen.”

Cardot couldn’t have known that the OSC was already building its own case. It alleged that, together, the Sharpes and McCoshen engaged in their own kickback scheme, orchestrating the secret transfer of millions of dollars from Bridging’s investment funds into their own pockets. The OSC believes most of the money Bridging said it advanced to A2A actually went to 7047747 Manitoba Ltd., a McCoshen company. Through a series of 14 transfers between 2016 and 2019, McCoshen and his numbered company are alleged to have funnelled close to $20 million back to David.

Most of the payments, it appears, landed in David’s personal chequing account mere days after McCoshen or one of his companies received loan payments from Bridging. More than half allegedly went into his investment accounts, while another couple million went into his personal banking accounts. The Sharpes spent more than $225,000 on cars, buying a Tesla and leasing two Bentleys. They completed nearly $2 million in renovations on their Toronto home. The OSC believes that some of the money went into Natasha’s account, and some went to certain Bridging employees—those who allegedly knew of, or helped cover up, the Sharpes’ supposed misdeeds. Rounding out the OSC allegations: the apparent misappropriation of funds involving loans to Ng and those through Gautam’s entities.

“The pressure to keep making the numbers and monthly distributions will push Bridging to even more deceit. Until one morning we will wake up and the house of cards will have fallen.”

In the early months of 2020, investigators say, the Sharpes scrambled to cover up their own fraud, doctoring dozens of documents and concealing the true nature of their bogus loans. But the walls were closing in. In September 2020, the Sharpes learned the OSC wanted to question them the following month. Likely fearful of what the OSC would unearth, David allegedly directed a Bridging employee to work with the company’s third-party IT team to permanently delete thousands of emails on Bridging’s server. He provided a list of 18 potentially incriminating search phrases, including “Sean McCoshen” and his numbered company, “7047747 Manitoba Ltd.” Once the task was complete, approximately 34,200 emails on Bridging’s servers had vanished. The commission says David asked the employee to perform another search in March 2021, using some of the same terms, before his second interview with the OSC a few weeks later.

OSC investigators questioned David over video. (Natasha did not join the call.) He denied any wrongdoing, claiming to know (or remember) very little about the inner workings of the company he ran. For hours, the two investigators asked David about Bridging’s more questionable loans, with most of the interrogation centring on Peguis, McCoshen and Ng. Initially, he told the investigators that he’d had no financial dealings with McCoshen beyond the loans Bridging had advanced for the A2A project; he portrayed them as legitimate. When investigators eventually showed him documentation that appeared to prove the money trail from 7047747 Manitoba back to David’s personal account, he said the near–$20 million he’d received from McCoshen had been loans for personal investments. Investigators pointed out the suspicious timing of the loans. “It certainly does not look good,” David acknowledged. “That’s for sure.”

Related: Hydro-Québec’s Billion-Dollar Power Struggle

Yet he still refused to admit he’d done anything wrong. He claimed to have a hard copy of a loan agreement between him and McCoshen at Bridging’s offices. Investigators demanded that he produce it by 5 p.m. that day. When his lawyer pushed back against the urgency, investigators responded that they didn’t want to give David time to doctor any documents.

At 8:14 p.m. that night, David’s lawyers emailed the OSC to say he had searched his office at Bridging but could not find the loan agreement. The next morning, the OSC asked the Ontario courts to put Bridging under receivership— not because the company was insolvent but because the commission believed the Sharpes couldn’t be trusted to run it. The move, it argued, would protect both Bridging’s investors and the public. The courts granted the application that day, and control of Bridging was handed over to PricewaterhouseCoopers. Within a week, both Sharpes were fired. David, by and large, stuck to the story he told the OSC. He expressed to media that he thought the commission had gone too far. “The need to put in a receiver is perplexing,” he said. “We are stunned by this.” Cardot, meanwhile, felt vindicated. “I was at my kid’s soccer game when I heard about the receivership,” he told me. “And I thought, ‘Wow, I wasn’t crazy.’”

As sanguine—and surprised—as David may have seemed, the OSC alleges he embarked on a pattern of behaviour designed to hide his tracks. During the summer, according to evidence presented by the OSC, David began to threaten Bridging employees against talking. The OSC says he texted and called people, leaving profanity-laden messages, and that he insulted some and threatened physical violence against others. Andrew Mushore—the company’s former chief compliance officer and a respondent in the case, who the OSC alleges helped David cover up some of the fraud—was a particular focus of David’s ire. In one voicemail, he allegedly told Mushore, “I hope you remember you signed off on all these deals, eh?” and also threatened, “I’m going to fucking pound your face!” (Mushore did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

Nearly a year after Bridging was put into receivership, the OSC released its formal allegations at the end of March 2022. Bridging and the Sharpes, once considered the invincible masters of risk, were accused of fraud, misappropriated funds, self-dealing and misleading investigators. Investors stood to lose more than $1.6 billion.

The Sharpes have denied the allegations against them. For nearly a year, they lobbied to get the case thrown out, arguing that the OSC committed an abuse of process when it publicly released a portion of David’s testimony with its receivership application. They were unsuccessful, and the hearing started in June of this year. It’s scheduled to stretch over 35 non-consecutive days, with the last in February 2024. Several former Bridging employees will testify in court, and so too will Rishi Gautam.

In September, Dennis McCluskey, a former senior adviser at Bridging since 2015 who also sat on the credit committee, made his appearance. He alleged that loan-approval documents were sometimes altered for reasons he found unclear. He also said that he and other credit-committee members were sometimes unsure what the money was really used for. He testified that he found one loan-approval process so strange that he forwarded copies of his approval feedback to his private email address. McCluskey said he also raised questions about the $32-million Ng loan—specifically why Ng’s name didn’t appear on any of the documents—but his concerns were dismissed.

The Sharpes, however, will not appear and have refused to participate in the proceedings against them. They both claim not to trust the fairness of the Capital Markets Tribunal based on the OSC’s release of David’s testimony. (Tribunal hearings themselves are public; compelled testimony given to the OSC, prior to any official hearing, is usually not.) David has since vowed to pursue the matter of his testimony in court, even as the OSC case marches on. One of his lawyers, Brian Greenspan, told CB that David looks forward to challenging the OSC in court and believes the OSC violated his Charter rights. “These Charter violations are magnified as Mr. Sharpe is First Nations,” Greenspan said in a written statement, “and in light of the history of the violation and indifference to the rights of Indigenous people by government.” Natasha’s lawyers, meanwhile, did not respond to interview requests.

Ultimately, as noted in Greenspan’s statement, David believes that when it comes to Bridging, the real problem—the real travesty for investors—is the forced, “OSC-instigated” receivership. Before the company was put into receivership, he claims, Bridging was taking steps to add new board members and rectify certain OSC concerns. This would have preserved the value of the company’s funds, he insists, and kept it in the hands of “expert management.” Instead, he argues, the receivership will likely end in a lose-lose situation for everyone but PwC—which, he alleges, will profit from “unreasonable and egregious fees.” In his mind, the blame has landed at the wrong feet. “The receiver has focused on a wealth-destroying litigation strategy with no regard for investors,” he said via Greenspan’s statement. “The real story here is the conduct of the OSC and the conduct of the receiver.”

In the meantime, both McCoshen and Ng—the latter of whom was fined $5 million by the IIROC and is also facing criminal fraud charges—have disappeared. Ng did not show up to his Toronto hearing in the late spring of 2022 and refused to cooperate in the investigation. His ex-wife has filed a lawsuit against him alleging that he created a bogus family trust—used to hold millions in heavily mortgaged properties—shortly after the regulatory investigation. Its supposed real purpose: to help Ng evade his creditors. (Ng has denied these accusations, as well as the criminal allegations against him.)

That Bridging operated so boldly, and with such impunity, speaks not just to insufficient oversight but also to a financial industry laser-focused on cartoon dollar signs

McCoshen is now likewise averse to the spotlight he once chased. The day before David Sharpe gave his fateful OSC testimony, McCoshen appeared before the House of Commons transportation committee, promising the many benefits of his railway project. He spun his well-worn yarn about wanting to help First Nations. It was the last time he was seen in public. Through his lawyer, McCoshen has refused to answer any of PwC’s many questions, claiming that he’s too ill to speak. In August 2021, he filed for bankruptcy in Oregon, stating that he was, until shortly before filing, living in a medical-care facility in B.C.

Related: How Canada’s Crumbling Health Care System Opened the Door to For-profit Virtual Care

Bridging’s failure triggered a cascade of lawsuits against other companies and people within its orbit. In an attempt to recoup some money for Bridging investors, PwC sued Peguis First Nation, its chief and its council, as well as two corporations created by the First Nation, for $170 million in early 2023. (Representatives for Peguis did not respond to requests for comment.) A few months later, PwC launched another lawsuit, this one against KPMG, the multinational accounting giant responsible for auditing Bridging’s income funds. PwC is suing the firm for $1.4 billion. It alleges that if KPMG had done its job properly, it would have caught the Sharpes’ alleged financial con. Or, as PwC puts it in the lawsuit: “Throughout KPMG’s tenure, the Bridging funds materially misrepresented the value of their assets and financial performance. KPMG negligently failed to detect and report on these misstatements.” (In a statement, a representative from KPMG wrote: “KPMG takes its role and responsibilities as auditor very seriously and stands behind its work as auditor of the Bridging funds. We have never been the auditor for the Manager, Bridging Finance Inc. We are confident in our audit work and will vigorously respond to the allegations made in the statement of claim.”)

But it isn’t just Bridging’s receiver that’s petitioning the courts in the wake of the fallout. One B.C.- based railway company, G Seven Generations, filed a lawsuit against David Sharpe alleging that, after several meetings in 2015, McCoshen and Sharpe stole proprietary route information and used it to plan the A2A project. The railway’s CEO, an Indigenous man named Matt Vickers, claims the fledgling business relationship fell apart after he refused to give McCoshen a kickback fee for arranging a potential loan with Bridging. Even the RCMP has started an investigation against Bridging, although no charges have yet been laid.

As the OSC hearing continues, the lesson is already clear, and it’s an old one: If something seems too good to be true, it probably is. That Bridging operated so boldly, and with such impunity, speaks not just to insufficient oversight but also to a financial industry laser-focused on cartoon dollar signs. The process, the details and the real cost of risk often appear to matter much less. David and Natasha Sharpe told investors, regulators, auditors and the media that they, and their friends, were savvy deal-makers with hearts of gold. For years, everybody believed them, simply because they wanted to.