In 2015, Massachusetts’ newly elected Republican governor, Charlie Baker, flew to St. John’s for his first-ever New England Governors and Eastern Canadian Premiers summit, an annual gathering focused on the joint challenges facing New England, Atlantic Canada and Quebec. One of the big topics of discussion that year was climate: how these 11 provinces and states would work together to drive down their greenhouse-gas emissions. For Baker, that meant one thing above all: tapping into Quebec’s huge surplus of hydroelectric power to decarbonize his state’s energy grid, which is heavily dependent on polluting, expensive natural gas. “They have capacity,” he said in St. John’s. “We have demand.”

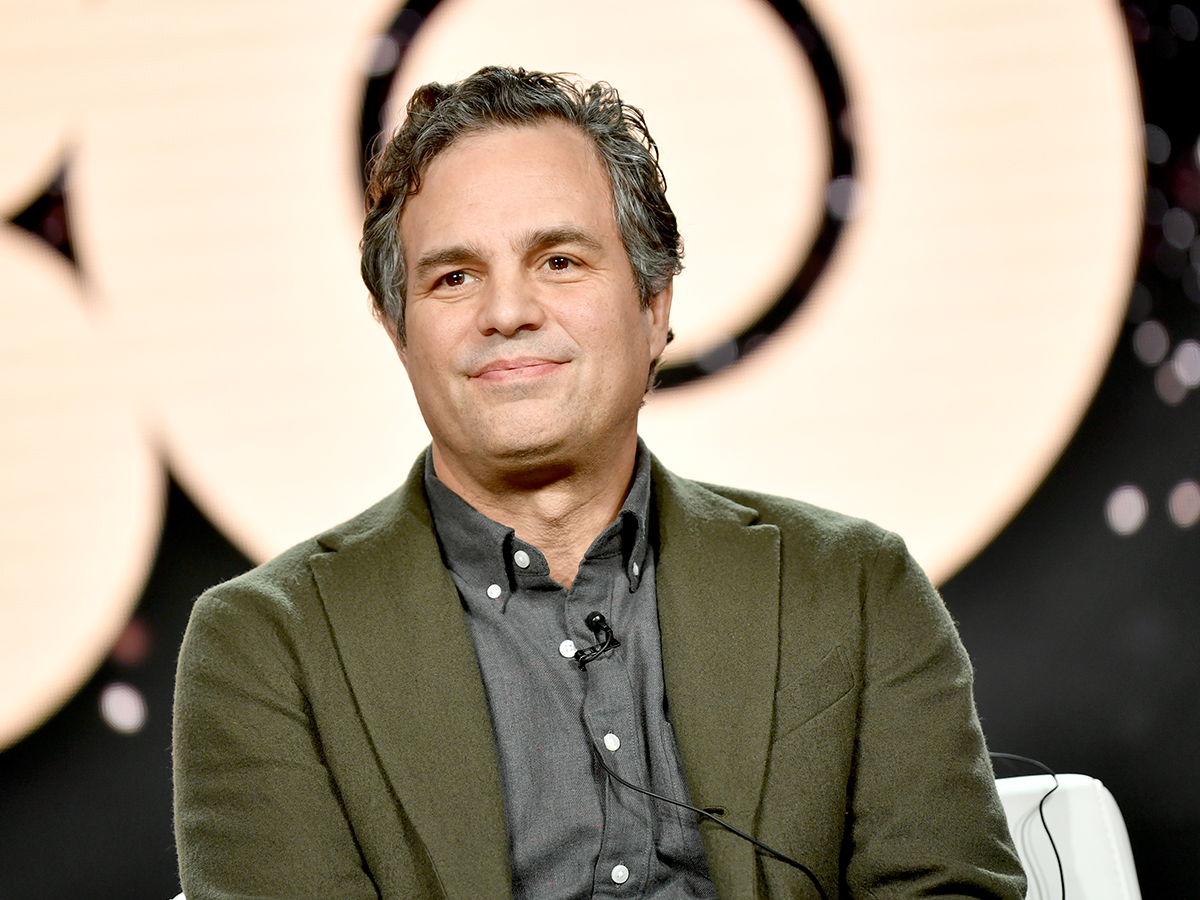

It’s not every day that a Republican governor makes a push for a transformative clean-energy proposal, but Baker—a defender of abortion rights, Obamacare and the Paris Agreement—isn’t a typical Republican. (He didn’t vote for Donald Trump.)

By 2017, Trump was using his executive powers to roll back the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Act as Baker was doubling down on his energy intentions. Massachusetts put an ambitious renewable-energy initiative out to tender. The state’s mandate was clear: All of its energy-distribution companies would have to enter long-term contracts to procure sustainable energy from wind, solar or hydro.

Massachusetts received 46 proposals in response to its RFP, and, indeed, six came from Hydro-Québec, the Montreal-based public utility with a long history of making enterprising energy deals. Among the six was New England Clean Energy Connect (NECEC), a proposal to build 832 transmission towers that would carry 233 kilometres’ worth of high-voltage line from the Quebec border to a converter station in Lewiston, Maine—which in turn would deliver 1,200 megawatts of power to Massachusetts and billions of dollars to Hydro-Québec’s coffers.

Submitted in partnership with Connecticut-based energy company Avangrid, the plan would reduce Massachusetts’ greenhouse-gas emissions by 3 million tonnes annually—the equivalent of 700,000 cars’ worth of pollution. Some Massachusetts taxpayers grumbled at having to fund the entire US$950 million construction. But that was nothing compared to the major source of controversy around the project: the high-voltage transmission corridor would have to cut through wetlands and forests in Maine.

Since 2018, NECEC has been dogged by fierce opposition from an unlikely—and ideologically fragmented—coalition of incumbent fossil-fuel interest groups and fossil-fuel environmental groups in Maine. The former brought money to the fight; the latter waged war on ethical and ecological grounds. Both positioned Hydro-Québec as the foreign bogeyman: a state-owned monopoly bent on mowing down forests in pursuit of profit.

“Hydro-Québec is just full of shit,” says Nick Bennett, staff scientist at the Natural Resources Council of Maine, a conservation group that stridently opposes NECEC. For starters, he doubts that the plan will reduce the emissions outlined in its projections. “These people have lied to an unbelievable degree.” (Hydro-Québec begs to differ.)

In January 2021, after three years of consultations, town hall meetings and environmental analysis, the project cleared its final approvals and began construction. Ten months later, the sheer volume of opposition convinced legislators in Maine to hold a referendum on whether NECEC should, in fact, proceed—even though construction was already far along and money invested. One-third of Maine voters came out to the polls, and the vote came in at 59 per cent opposed. Avangrid immediately challenged the referendum’s legality, saying that retroactively banning an approved project violated both state and federal law. After that, the final decision was punted to the Maine supreme court.

“‘Frustrating’ doesn’t even begin to describe how this feels,” says Serge Abergel, the 49-year-old chief operating officer of Hydro-Québec’s U.S. operations. “It has been an enormous weight on the shoulders of all the people who’ve worked on this for years and years.”

The stakes are high—not just for Massachusetts but for Quebec and potentially the entire region. Hydro-Québec had been exporting power to New England since the 1980s. NECEC is not only a multi-billion-dollar export project but also the key to a long-term play by Hydro-Québec to become an indispensable force on the power grid.

“It has been an enormous weight on the shoulders of all the people who’ve worked on this for years and years”

But there are many opponents: Fossil-fuel companies are fighting off a threat to the bottom line. Canadian Indigenous communities, for their part, are taking this moment to draw attention to historical injustices. To them, NECEC is another example of Hydro-Québec profiting from the historical exploitation and destruction of their traditional lands, upon which many of today’s hydroelectric facilities are built. For environmental groups in Maine, it matters more that NECEC is disrupting a delicate landscape and less that it is a clean-energy project. The irony here is evident. Building green will always have an impact. The key point that NECEC illustrates is this: What trade-offs and collateral damage are we willing to take on to decarbonize our energy system and attempt to stave off a climate catastrophe?

For many climate advocates, the pitched battle over a few hundred kilometres of high-voltage line has therefore become a litmus test, prompting bigger questions: What’s the cost of a clean-energy grid? And how ready are we to put into motion an energy transition that is becoming more urgent with every passing year?

“Can I share my pain with you?” asks Serge Abergel over the phone from his soon-to-be-empty Montreal home.

Abergel took over the job as Hydro-Québec lead in the States last December. He is now, in the words of Hydro-Québec CEO Sophie Brochu, “patrolling the waters” stateside, drumming up support for—and dousing opposition toward—the company’s ambitions in New England. So he’s house-hunting there. Ideally, his new home base will be central to Montreal, Boston and New York but close as well to the pastoral New England settings where Hydro-Québec’s plans have been most bitterly contested. It hasn’t been easy.

“You see a house in the morning, and in the afternoon the agent tells you the owners are expecting offers by tomorrow noon,” he says. “Like it or not, you’re a foreigner, a Canadian. You have no clue what this market is.”

Abergel may as well be talking about Hydro-Québec’s reception in Maine, where its status as one of the world’s largest hydroelectricity systems—and a state-owned monopoly—has given rise to a David and Goliath narrative.

Not that there isn’t something of Goliath in the company. Over the past 80 years, it has built on vast swaths of Quebec, harnessing the power of hundreds of wild rivers with 681 weirs and dams, 61 generating stations, 260,000 kilometres of transmission line and 28 hydro reservoirs—“inland seas,” in Hydro-Québec’s words. The largest, Caniapiscau Reservoir, is Quebec’s biggest body of water, covering more than 4,300 square kilometres.

It’s impossible to separate Hydro-Québec’s impact from Quebec’s modern history. In 1962, Liberal leader Jean Lesage campaigned on a promise to bring Quebec’s few remaining private utilities under Hydro-Québec’s control, fully nationalizing an energy sector previously dominated by Anglo and American concerns. “Masters in our own house” was Lesage’s slogan. Hydro-Québec became a symbol of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution—and a cash cow for the province, with the majority of its profits, including a record $3.5 billion in 2021, redistributed to the Quebec government, its only shareholder.

In 2015, Hydro-Québec appointed veteran Bombardier executive Eric Martel as its CEO. Martel articulated a new vision for the utility to become “the battery of the northeast,” a defining force uniting the balkanized electrical systems of Quebec, Ontario, Atlantic Canada, New England and New York—and their roughly 60 million residents. Here’s how it would work: By building more transmission lines to the northeast grid, Quebec would export power but also import it when renewable generation is high in New England. Hydro-Québec would then fill its reservoirs rather than using that water to generate power. And when the opposite conditions occurred—when the wind wasn’t blowing or the sun shining and New England states weren’t producing enough clean energy—reservoirs would be drained to generate power for export.

In 2020, Martel left Hydro-Québec to return to Bombardier as president and CEO, and he passed the baton to Sophie Brochu, who had previously spent 12 years as CEO of natural-gas distributor Énergir (formerly Gaz Métro). She ran with it. Brochu has long focused on the urgency of the transition to green power. Jean-Benoit Nadeau, a journalist who has written extensively about the energy sector, profiled Brochu for L’actualite in 2017. That story positioned her as a corporate leader with an unusually strong ethical sensibility. “Brochu explains that her job is to ‘optimize’ performance—financial, social, environmental—rather than to maximize profit,” wrote Nadeau.

Brochu’s social conscience appears genuine, but it is also clear that she’s selling something. “People grasp the fires in California. People grasp the fires out west. People get the need,” she says. “But we collectively have to be way more curious about what will be required to make the energy transition happen. Human beings don’t like to hear this, because it means ‘What will be necessary for me? What will I need to change?’”

For Brochu, the answer is building more transmission capacity, enabling more energy-swapping with other jurisdictions and facilitating the most efficient allocation of clean energy. And before any of that can happen, states and provinces need to stop being territorial entities—“parochial, autonomous little systems,” as Brochu calls them.

The problem, of course, is that you can’t run power into Massachusetts without going through another state. The first attempt to bring Hydro- Québec’s electricity to Massachusetts was called Northern Pass, a proposed line through New Hampshire. It was rejected in 2018 by state regulators due to concerns about impacts on the state’s White Mountain National Forest. NECEC was the second choice, and again Hydro-Québec was ready for a fight, having long faced opposition to new infrastructure. In 2004, the activist group Résistance Internationaliste claimed responsibility for bombing a Quebec hydro tower, protesting the “pillaging” of natural resources by the U.S.

Bombings aside, these experiences usually had diplomatic and productive outcomes. And according to Abergel, they instilled in Hydro-Québec’s corporate brass the idea that honest conversation about benefits and drawbacks could win hearts and minds. He sounds like he really believes it—or did. “Nothing,” Abergel says now, “prepared us for Maine.”

Among the earliest opponents of NECEC was Sandi Howard, an eighth-generation Mainer who works as a whitewater guide in The Forks region—right near the intersection of the Dead and Kennebec rivers, where NECEC would pass. In July 2018, she attended one of the first consultations, at The Forks Town Hall, packed with business owners, river guides and outdoors enthusiasts, most of whom she knew. “It’s a very small community here,” she says.

After that first meeting, during which, Howard says, the project was pitched as a done deal, she began a Facebook group called “Say No to NECEC.” It now has more than 11,000 followers and has become a clearinghouse for opposition.

The foremost concern was location. Most of the corridor was to be built alongside an existing line, but an 85-kilometre section would be newly constructed through Maine’s North Woods. Howard and others were worried about tourism and recreation—fishing, hiking, rafting—as well as the ecological impacts of cutting a 300-foot-wide path through intact forest.

Clearly, there would be impacts. An environmental assessment by the U.S. Department of Energy declared the affected area part of “one of the world’s last remaining contiguous temperate broadleaf-mixed forests” supporting “exceptional biodiversity.” The question facing regulators boiled down to one premise: Does the project’s benefits outweigh its harms? The Department of Energy’s assessment, and another by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, concluded that the answer was yes. The former pointed to measures suggested by Avangrid to mitigate harms, such as taller-than-usual towers, placed farther apart, to minimize disruption at ground level.

But there still would be consequences, particularly habitat fragmentation, with that large, contiguous forest being sundered in two. Serge Abergel’s position, essentially, is that we don’t have time to craft ideal, impact-free solutions: “Anybody that promises to build large-scale infrastructure today without issues is either very naive or lying.”

The argument may be self-serving, but it’s not necessarily false. New transmission corridors must traverse continents, cutting through untrammelled wilderness. Solar and wind farms require vast tracts of land. Electric vehicles require the destructive extraction of metals and minerals. When it comes to NECEC, there are those who doubt that all the construction will amount to much upside. “We quickly determined that NECEC had no evidence of any climate-change benefits at all,” says Nick Bennett of the Natural Resources Council of Maine. “This is just a shell game by Hydro-Québec.”

Bennett and others have argued that Hydro-Québec does not have adequate surplus power to serve both Quebecers and the new contract without reducing spot-market sales in other jurisdictions, such as Ontario. The result, they say, is that those markets would be forced to compensate with fossil fuels. This “resource shuffling” argument has been a cornerstone of advocacy against NECEC and Northern Pass as well as Champlain Hudson Power Express—Hydro-Québec’s other big U.S. export project, which is intended to deliver 1,250 megawatts of power to New York City. Anti-NECEC advocates cite the basis of the argument as unvarnished fact, whereas most energy-market analysts and climate researchers view it dubiously.

Ultimately, the fact that the project has become so bogged down illustrates how difficult the transition to clean energy will be. Emil Dimanchev, a climate-policy scholar at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and research affiliate at MIT, says that the controversy around NECEC “bodes poorly for our ability to meet our climate goals in the U.S. or Canada. We need to get good at building things again, and this is showing that we, as a society, are not good at building things.”

Dimanchev stresses that for the project to achieve its maximum potential climate benefits, it needs to be adaptable to a two-way system. That’s the driving idea behind his 2020 paper “Two Way Trade in Green Electrons,” which Hydro-Québec cites in its own PR materials. In that study, Dimanchev and colleagues investigated different models of how Canadian hydro would best be used to green the American grid. Their results were consistent with the so-called “battery” notion: Climate goals are achieved at the lowest cost if Quebec is not only an exporter but also an importer of energy, with the flow switching back and forth on the transmission lines.

This exact model is often touted by Hydro-Québec as a rationale for building more transmission, but NECEC is currently a one-way project, which frustrates Pierre-Olivier Pineau, the Energy Sector Management chair at HEC Montréal, the graduate business school at the Université de Montréal. He supports NECEC but also says it’s a piecemeal approach.

“Anybody that promises to build large-scale infrastructure today without issues is either very naive or lying”

“There is no credible future in which we will regret having built the transmission line to Massachusetts,” says Pineau. “Even if it is one-way now, it can become a two-way line easily. So I see it as a good starting project. At the same time, when I talk to Hydro-Québec, they just say ‘We want to be the battery of the northeast.’ So how do you make that happen?”

A final refrain among opponents is that Hydro-Québec’s power is not, in fact, nearly as clean as advertised. This point is tricky to pin down. Hydro reservoirs—those inland seas that Hydro-Québec is so proud of building—emit large volumes of greenhouse gases, especially in years immediately following flooding, as vegetation and other biomass trapped beneath the water decompose. Researchers calculate hydro energy’s impact on climate by estimating CO2-equivalent emissions, such as those from methane, over a hypothetical 100-year reservoir lifespan. By that measure, Hydro-Québec estimates that its entire power system has a carbon footprint of 32 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt hour—far below, say, coal, at over 1,000, and comparable to solar, which is typically between five and 50 grams.

There’s intense disagreement on the numbers. In testimony to the Army Corps of Engineers in 2019, Bradford Hager, a professor in the department of earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences at MIT and a prominent voice in this debate, cited the work of Swiss researchers Stephan Pfister and Laura Scherer in estimating lifetime emissions for the world’s 1,473 hydroelectric plants. Published in 2016, the research showed that Hydro-Québec’s facilities’ impact ranged from 42 to 605 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt hour. The exception was its Brisay generating station, on the Caniapiscau Reservoir in James Bay, which came in at a staggering 2,250 grams. This was enough, in Hagar’s estimation, to call Hydro-Québec “among the dirtiest hydro in the world.”

But according to lead researcher Pfister, this is a flawed conclusion. “Building hydro power will basically cause five years of damage,” he says. “The longer you run it, the lower the impact of kilowatt hours.” Because the vast majority of greenhouse gases are released immediately following a reservoir’s impoundment, average lifetime emissions are dramatically weighted to its first few years. In Iother words, Hydro-Québec’s reservoirs don’t have a high carbon footprint today—they used to. This may call into question the wisdom of building new reservoirs, but it also means that refusing to make use of the power they produce today would be environmentally nonsensical.

“I question where the opponents come from with their claims,” says Abergel. “And I think a lot of them, unfortunately, are likely to be paid actors in this. There is genuine opposition, but there is opposition that’s professional as well.” This is a not-so-veiled reference to the incumbent oil-and-gas companies that have provided the lion’s share of the money to opponents of NECEC. Those companies find themselves in an unusual alliance with non-profit environmental organizations and back-to-the-land New Englanders.

Sandi Howard acknowledges the bedfellows. After six months of grassroots organizing, largely through her own personal networks, Howard allied with environmental networks: Natural Resources Council of Maine, Sierra Club Maine, Appalachian Mountain Club, Trout Unlimited and Environment Maine. A few months after that, she found she had better-funded allies: incumbent fossil-fuel producers, including two Texas-based fossil-fuel companies, Calpine and Vistra, and Florida-based NextEra Energy, whose New England operations largely consist of oil and gas plants. Howard says it was necessary to ally with well-funded backers to take on a powerful entity like Hydro-Québec. “Unfortunately, private citizens just don’t have the deep pockets that multinational corporations do,” she says.

The growing anti-NECEC coalition began working in 2020 to organize the referendum that put the fate of the project directly in the hands of Mainers. An initial effort in 2020 was rejected by a judge—but a second attempt landed the question on a ballot last November. For months, both sides mounted a PR campaign, spending tens of millions of dollars. “I began to dream about it at night, literally,” says Abergel.

The opposition side included Mainers for Local Power, a group funded by Calpine and Vistra, which spent nearly US$26 million. Another group, Stop the Corridor, is an alleged dark-money organization that has not disclosed its donors. But it, too, ran radio and TV ads featuring folksy small-town Mainers fretting that the project will degrade Maine’s “environment and outdoor heritage…all to send power to Massachusetts,” complete with photo collages of earth-moving equipment tearing apart pristine wilderness.

Proponents spent even more—US$70 million, including US$22 million by Hydro-Québec—on similarly over-the-top marketing. (An Avangrid-backed letter campaign aimed at rural Mainers suggested that allowing referendums to retroactively amend laws might result in revoking constitutionally enshrined gun rights.)

There was one more wedge used by opponents to paint Canadian hydro as unsavoury, however, and it was much harder to ignore than spuriously interpreted data about dirty hydro. In 2020, five Indigenous communities in Canada banded together to publicly oppose Hydro-Québec’s export efforts. If the history of Hydro-Québec’s ambitions mirrors the history of the province itself, so too does it mirror the darkness of that history. Many of Hydro-Québec’s reservoirs and other projects were built on traditional Indigenous land. Some of those communities are now using the furor over NECEC to draw greater attention to those past injustices—a strategy that has won sympathetic ears in New England.

The most dramatic example is the behemoth Smallwood Reservoir, which is not actually in Quebec but just over the border in Labrador. Created in the early 1970s, it’s the second-largest hydro reservoir on earth, containing 33 cubic kilometres of water held back by 88 dikes. It feeds the nearby Churchill Falls Generating Station, a joint project between Hydro-Québec and Churchill Falls (Labrador) Corporation Limited, a Newfoundland-based Crown corporation established to build the facility. Since 1974, nearly all the electricity generated at Churchill Falls has been sold to Hydro-Québec.

“This was devastating, and it completely changed their way of life overnight”

Before it was flooded, the 6,500-square-kilometre area of land—larger than Prince Edward Island—covered by the Smallwood Reservoir was a dense patchwork of spruce forests, small lakes and wild rivers. It was inhabited primarily by the Innu Nation of Labrador, for whom it was an integral part of a traditional way of life, used for travel, hunting and sustenance. The Innu Nation has thousands of years of history here—after the reservoir was flooded in 1974, the bones of interred Innu washed up on the reservoir’s shores for years.

“There was no consultation and in many cases not even notification that this land, which the Innu had and continue to have title to, would be flooded,” says Matt McPherson, a lawyer with Toronto firm Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP, which is representing the Innu in a $4-billion lawsuit against Hydro-Québec. “This was devastating, and it completely changed their way of life overnight. In many cases, Innu people only learned about it when the water started rising.”

Similar issues have played out in Quebec. “We have many kilometres of hydro lines crossing unceded ancestral territories, and our sovereignty over the land is still effective to this day,” says Lucien Wabanonik, councillor with the Lac Simon band council in western Quebec and member of the Anishinabeg Nation.

When Sophie Brochu joined Hydro-Québec in 2020, she pledged to make outreach to Indigenous communities a foremost concern. “I came to Hydro-Québec with no knowledge of Indigenous reality,” she says. “I’m 59. I was raised by people who didn’t know what they were talking about—the history, the relations.” She says she wants to ensure that younger Quebecers get a well-rounded sense of the history of Hydro-Québec, because the older generation still clings to its mythic role in the Quiet Revolution narrative. “My dream is that each kid could go up and visit James Bay and take the time to sit down with the Indigenous communities and understand their reality,” says Brochu.

Wabanonik says that those pledges have not yet amounted to much, and he doesn’t see the issue as being especially complicated. He also says that claiming ignorance of the history doesn’t wash. “I don’t understand why a person like that, with that type of education, is saying ‘I wasn’t aware,’” he says. “To me, that’s an excuse.”

After the referendum in Maine last November, the work on building NECEC ceased, and its construction licence was suspended. In December, Avangrid appealed the decision to Maine’s Supreme Judicial Court. On August 29 of this year, the court issued its ruling, siding with Hydro-Québec and Avangrid—sort of. It declared the retroactive ban to the project illegal—subject to proof that construction was sufficiently far along before the referendum. It now falls to the Maine Business and Consumer Court to decide if the work that has been completed between the project’s approval in January 2021 and the November 2021’s referendum is “significant, visible construction and in good faith.” That seems like a shoo-in. NECEC has already spent US$450 million, cleared most of the corridor and built 120 towers. All the same, opponents have vowed to not stop fighting.

Even if that decision is ultimately favourable to NECEC, other obstacles remain. Opponents also took the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands to court, arguing that the bureau didn’t follow proper procedures when leasing land to Avangrid for its corridor. In August 2021, a Maine judge agreed and vacated a lease to one mile of public land. That isn’t necessarily a death blow for the project, but it will add more time, complexity and cost to the approval process.

Opponents, from Sandi Howard and the Natural Resources Council of Maine to NextEra, have also mounted appeals against NECEC’s environmental approvals and are aiming to consolidate those appeals into one. “The public should have an opportunity to have self-determination on how we’re going to meet our climate goals,” says Howard. “Jumping at the first project is not always the way that it’s going to go. It’s a very complex problem.”

Serge Abergel counters that this is merely an excuse for inaction. “NIMBYism is looking at the tree and saying ‘My tree in Maine, you’re never touching it. That’s how I protect the environment,’” he says. “And that’s how we’re doomed to fail. Any transition will be costly. You’re doing open-heart surgery here. It’s going to hurt. There’s no space for NIMBYism here.”

Ultimately, the goal of naysayers is to either kill the project or delay it indefinitely. And it’s this that makes the NECEC battle emblematic of the challenges of green energy. In a widely publicized 2021 study, Princeton University researchers detailed just how much had yet to be done on the energy transition, concluding that technology and infrastructure must be deployed faster and at a larger scale than ever before. Given that renewable energy tends to have a larger footprint on land area than fossil fuels, vast wind and solar farms and thousands of kilometres of transmission line must be built in rural areas. Doing this requires faster approvals than the traditional environmental analyses and community consultations allow without ignoring truly significant ecological impacts or throwing social licence out the window.

It’s also possible that Hydro-Québec could have helped along its own case by having an on-the-ground presence in the U.S. earlier—Abergel, or someone in his shoes, should probably have been house-hunting before the pandemic. “One of their mistakes has been to try to conduct this without being present,” says Quebec journalist Jean-Benoit Nadeau. “They were essentially subcontracting the representation to someone who was not them.” (That someone is Avangrid.)

In any case, Abergel is there now—and for the long haul. If NECEC is ultimately rejected, there is still another potential route through another state: Vermont. This would require new permits and more years of discussion and approval—a prospect that Abergel, after years of fighting for NECEC, doesn’t seem to relish. In September, he put an offer down on a century-old house near Lake Placid, in upstate New York. There, he hopes to find something of an American refuge—a place to bide his time, waiting for the next round of court decisions—and whatever appeals or battles follow.

“I like renovations,” he says. “It’s like therapy. By mid-October I should have the house and something to do that takes me away a little bit from all of this. I hope.”

This article appears in print in the fall 2022 issue of Canadian Business magazine. Buy the issue for $7.99 or better yet, subscribe to the quarterly print magazine for just $20.