Scammers Are Posing as Recruiters on LinkedIn and Swindling Job Seekers

In December, David, a Toronto-based regional manager for a tool company, had to be the bearer of bad news to several job seekers who thought they’d landed employment with his company.

A few months earlier, David and his team noticed several puzzling calls coming into the organization’s general contact line. All the callers asked to speak with the human resources department about roles they said they’d been hired for. They all cited a recruiter by name—one who really did work with the company—but said they had been given no direct contact information for them during their recruitment. This was unusual for the company’s hiring process, and when the calls were flagged by HR, the department confirmed the roles didn’t exist.

And then there were the walk-ins.

“We had five or six people show up in our lobby on what was supposed to be their first day, saying, ‘I’m here for my job.’ It was right before Christmas and it was really crushing to talk to these people,” recalls David, who requested to use his first name only as he isn’t authorized to speak on behalf of his employer. “There were so many stories of, ‘I told my wife and my family and friends about this great new role, and now I’m going to have to go back and tell them I’ve made a fool of myself.’”

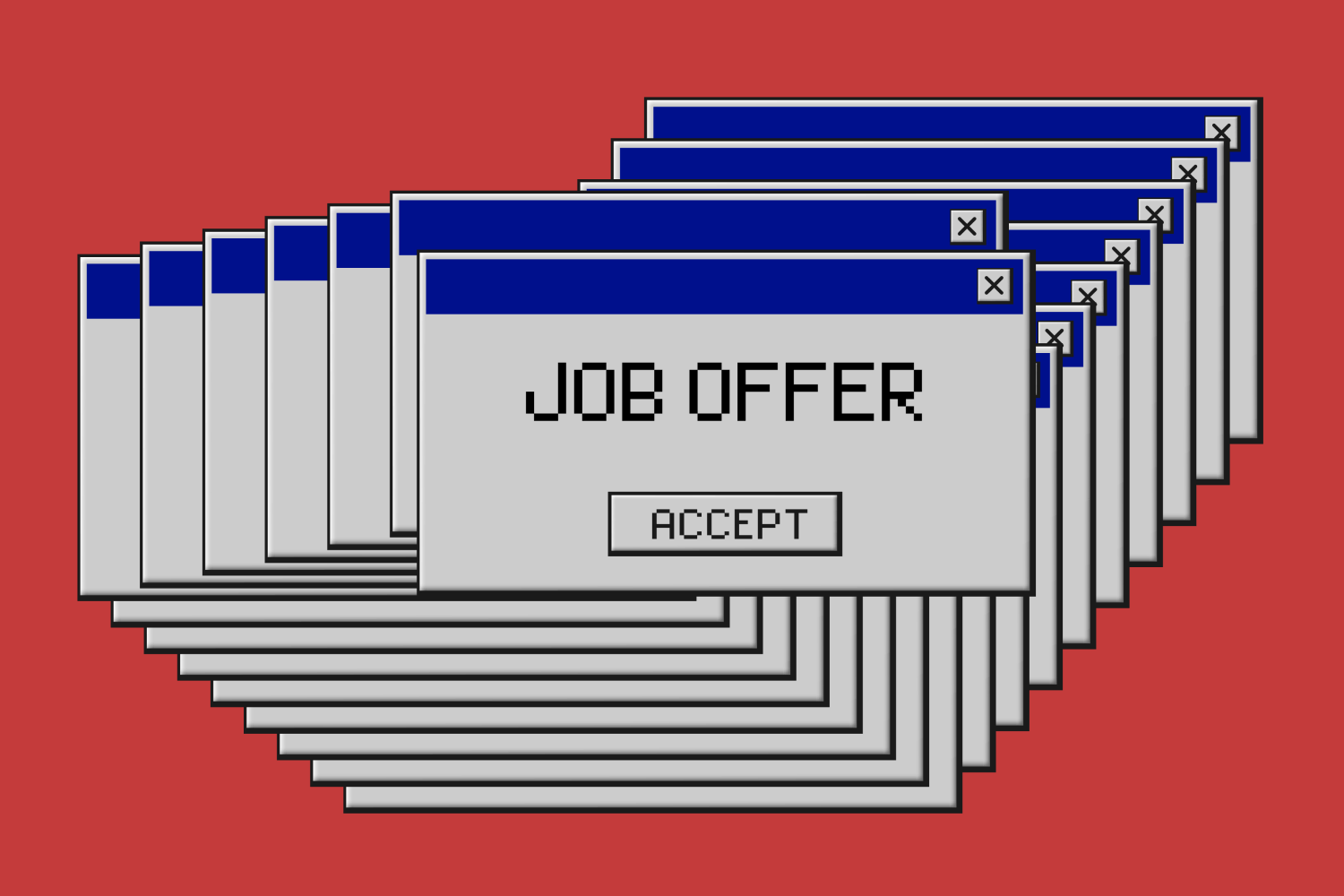

The job seekers were the victims of recruitment scams—something that fraud and employment experts say has become much more prevalent since the onset of the pandemic and the remote work boom. While the details can vary, most job scams follow a similar script: Scammers pose as hiring managers or recruiters, often scraping the details of real recruiters for a given company to create authentic-looking profiles on sites like LinkedIn. Then, they reach out to job seekers about employment opportunities, or post fake job listings online. Jeff Horncastle, communications outreach officer with the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC), says scammers might even create an alternate web presence for a company by changing the domain name subtly, such as replacing the letter “I” with a lowercase “L.”

Lured into a false sense of safety, job seekers go through a virtual interview process and quickly receive a job offer, often at the upper limits of the market rate for that position, and are asked to provide personal information such as their social insurance number and driver’s license—which can lead to identity theft. The federal government says employment scams are also often fronts for illegal money laundering or pyramid schemes. In some cases, applicants are provided with a cheque and instructions to deposit it in their account and e-transfer some or all of the money to a third-party for services, such as on-the-job training. After the money is sent, the bank will reverse the deposit because the cheque is fraudulent.

This ruse is what happened at David’s company. David says the victims he spoke with received an offer letter in the mail and were sent a cheque with an amount of around $4,000, which they were asked to deposit and then pay to a job-training company. While the amount on the cheque would initially appear in their account, the cheque eventually bounced—after victims had already e-transferred the funds.

The impact of job scams

Canadians lost $7 million to job scams in 2022, according to the CAFC. While that was down slightly from a high of $9.4 million in 2021, both years well exceeded 2020’s losses of $4.4 million. Horncastle says that job scams are consistently among the CAFC’s annual top 10 scam types based on number of reports and dollars lost. But the centre believes that scams are dramatically underreported, and the official numbers represent just five to 10 per cent of actual losses.

LinkedIn, the world’s largest professional network, has seen scams get increasing “clever,” Oscar Rodriguez, vice-president of product management at LinkedIn, told the Financial Times in February. “We see websites being set up, we see phone numbers with a seemingly professional operator picking up the phone and answering on the company’s behalf,” Rodriguez told the outlet. “We see a move to more sophisticated deception.”

In its most recent transparency report, LinkedIn said between January and June 2022, it had blocked 16.4 million accounts suspected of being scammers, restricted 5.4 million “proactively” before any members had reported them, and 190,000 after LinkedIn users had flagged them.

While LinkedIn has been public about its crackdown on job scams, Mike Shekhtman, a Vancouver-based senior regional director at employment agency Robert Half Canada, says they’re also occurring on other job boards and career sites, like Indeed, as well as social media sites like Facebook—and even on Craigslist.

Horncastle says job seekers across the board, particularly ones that have posted their résumé and indicated they’re looking for work, are being targeted by scammers. Shekhtman says that while “scammers don’t discriminate,” Robert Half has seen that they tend to go after two vulnerable groups: early-career professionals who don’t have enough work experience to identify unusual recruitment practices, and new Canadians. “Some scams we’ve seen have grammatical errors that might not raise a question early on for someone whose first language is not English,” he says.

Job scam red flags: Things to look out for

Horncastle says common job scam red flags include being offered a job immediately after the interview, or receiving an emailed job offer without an interview, which the scammers will claim is due to the job-seeker’s skills. No legitimate employer will request that an applicant accept or deposit funds, he adds—even for training.

Shekhtman encourages job seekers to pump the brakes if they’re to provide personally identifying information to a recruiter before they’ve formally accepted a role. “There’s no situation where you should be giving your SIN, your banking information or your driver’s license until you’ve been hired,” he says.

He says applicants should spend time doing their due diligence on a company’s website, ensuring they’re being contacted by someone with an email whose domain name matches the one listed on the site. It’s also wise to run the company’s name and the word “scam” through a search engine to see if there are any warnings online.

On LinkedIn, users can use a new “about this profile” feature, which shows them when a profile was created and last updated, and whether the member has a verified phone number or work email. It also adds a warning message to some private messages if the recruiter asks to take the conversation to another platform.

David says that thankfully, his company hasn’t heard from any more scam victims since December. But after the alarming experience, the business added a disclaimer on job postings that all jobs require applicants to apply directly through the careers page on its website.