On a Friday night in August 2020, Arthur Keech was working late from his home office in Vancouver. Keech is an IT manager for Amacon, a large real estate developer. He had only been in the role for about seven months when he received a curious note from one of his colleagues: They had tried to open a network file but couldn’t. Keech figured it was an error—someone had screwed up a file name. But when he went to log into the company’s operating system, he couldn’t. “That’s weird,” he thought. He used a different login and managed to gain access, but he only needed to take one look to realize he had a big problem.

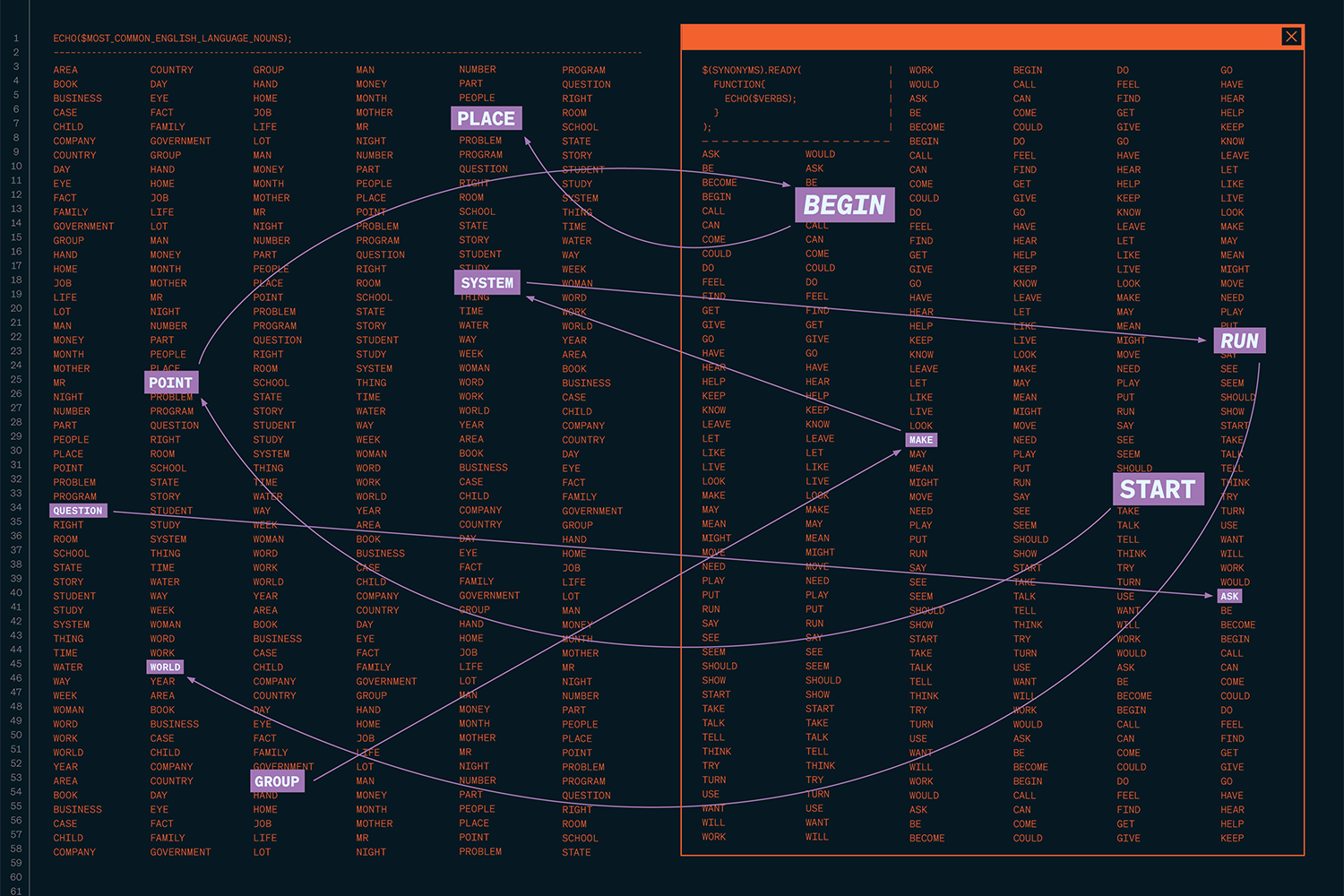

Keech immediately noticed that all of the file extensions had been changed from the standard .doc to “random garbage.” And when he tried to access any of the Windows files, a note popped up: “Hi! Your files are encrypted,” it began. Keech’s heart was pounding. He knew exactly what was happening: It was a ransomware attack. Someone, or some group of people, had exploited a technical vulnerability or used social engineering—like phishing—to hack into his company’s system. The note explained that Amacon’s files were locked and threatened to release them to the public. It also said that the hackers had exfiltrated some data, which they planned to leak onto the dark web—an underground version of the internet that is associated with all kinds of unlawful activities—unless Amacon paid up. They directed Keech to a URL that he could use to negotiate the final—at the time unspecified—amount and a Bitcoin wallet into which Amacon was to deposit the payment. “For us, this is just business,” concluded the message, which was signed by an anonymous entity called NetWalker.

The syntax was clunky and inelegant. The typos were glaring. The upbeat greeting, complete with an exclamation point, was incongruous with the demands being made—as was the insistence that it was nothing personal. The note gave the impression of both haste and careful planning.

But the message itself was clear: The business had been hacked and its data was now in the hands of someone controlling things remotely from somewhere in the world. But Keech knew something the ransomware pirates didn’t. At a previous job, he had been subjected to another attack. That experience had made him recognize the need for greater technical protection, so he made it his mission to build out robust security features in the event that something like that ever happened again at his workplace. He knew that it was difficult to completely shut down the possibility of ransomware attacks but that he could decrease the company’s vulnerability. In his time at Amacon, Keech also made cybersecurity his top priority. In fact, when the attack happened, he had just finished upgrading his systems by creating a series of offline backups, encrypting sensitive files, patching security vulnerabilities and testing disaster-recovery protocols.

Secure in the knowledge that all of Amacon’s files were backed up offline, Keech didn’t even bother interacting with the hackers. “It makes you feel like an IT superhero,” he says. Still, responding to the attack became an all-handson-deck situation. Keech and his team worked for three days straight to restore Amacon’s data and systems, searching for the vulnerability that the hackers exploited to gain access. Some of Amacon’s files were indeed released on the dark web, but thankfully none included sensitive material. Keech logged on and spent weeks trying to find the files in order to take them down, cruising past articles about how to make your own nuclear weapon. Keech, who describes security as an evolving process, set about implementing further safeguards, like proactively searching for weak points in infrastructure and strengthening them. But the majority of companies, public and private, are not in such a secure position because their cyber defences are less robust.

A year later, the RCMP contacted Keech. They had found the source of the ransomware attack. When he learned the identity of the hacker, he was shocked: It was Sébastien Vachon-Desjardins, a government worker in his 30s who lived in a tidy white home in Gatineau, Que. “The mental picture is generally of a hacker who lives overseas where intellectual-property laws and hacking laws are much looser,” he says. “I can’t picture any of the IT professionals I’ve worked with making that decision to become a hacker.” By day, Vachon-Desjardins appeared to be a productive—and harmless—member of conventional society, a clean-looking bureaucrat who drove a sensible car. But by night, he was a pirate for NetWalker, a ransomware network that includes affiliates from all over the world—and he was a particularly good one.

When Vachon-Desjardins was finally arrested in January 2021, he was charged with perpetrating similar attacks against a total of 17 Canadian victims—all public institutions or private businesses and most of whom either paid a ransom or suffered significant losses. Much has been made of Vachon-Desjardins’s prowess and the scale of his theft. But what his case demonstrates is not simply the damage of one particularly bad actor. Rather, it serves as a warning: Vachon-Desjardins is just one of many. There’s a virtual army out there—global and borderless—and there are plenty more attacks in store for our under-defended workplaces, critical infrastructures, public institutions and maybe even your own computer.

A ransomware attack feels like the call is coming from inside the house. One minute, an employee is working on a computer in what feels like relative privacy. The next, the files and systems they depend on start shutting down incredibly quickly. While the perpetrators hide behind complete anonymity, often operating from several time zones away, victims are suddenly technologically naked—all their information, vulnerabilities, strategies and secrets are scooped up and eligible for display.

“It’s analogous to someone breaking into your house, rearranging anything—everything—and then changing the locks so you can’t get into your own home,” says David Swan, one of the directors at the Cyber Intelligence Defence Centre at the Centre for Strategic Cyberspace + International Studies (CSCIS). And just as there are many ways to break into a home, so too are there many ways to break into a computer. One of the most common is simply sending an email with a link that, when clicked on, provides access to intruders. Once in, those intruders can download anything they want. More commonly, they lock it all down, so files might be visible but there’s no way to access them.

It’s at this very moment of panic and desperation that the “ransom” part of ransomware arrives. “The evil sticks its head up and says hi,” says Swan. “Someone will send a message either on your computer screen or through email saying ‘We’re the bad guys, and if you send us Bitcoin, we’ll give you the keys to unlock your files.’”

“I can’t picture any of the IT professionals I’ve worked with making that decision to become a hacker”

Canadian organizations have experienced their own fair share of hacks, including several recent high-profile events. In November, Nova Scotia’s Empire Company (which operates Sobeys, IGA, Foodland and other grocers) was subject to a cyberattack that shut down its network. The implications were enormous: Store and warehouse logistics were unmanageable, financial reporting impossible and computer systems inaccessible, with even in-store pharmacists unable to access information. Much of the business was frozen for a week, and Empire called in external cybersecurity experts. It’s estimated the attack cost $54 million.

In early February, a devastating ransomware attack shut down Indigo’s website and electronic payment systems. For weeks, visitors to Indigo.ca were greeted by a short message directing them to bricks-and-mortar stores, and the company said it was working with a third party to remediate damage. Experts opined that the business was losing millions, perhaps even tens of millions, as it grappled with the fallout. Later, news broke that employee data—including birth dates and social insurance numbers—had been breached. By late February, Indigo’s website was once again up and running but still at reduced capacity. Indigo made a public announcement that it had declined to pay the requested ransom to a group it had identified as Russian hackers.

And it’s not just private enterprise. In December, Toronto’s SickKids hospital was hit by a ransomware attack that delayed lab and imaging results and shut down phone lines—what the organization later referred to as a “Code Grey.” Families, many of whom were undoubtedly under unbearable stress, were also told to expect delays in diagnostics and treatment. By early January, about 20 per cent of the priority systems that have a direct impact on hospital operations had yet to be restored.

Ransomware attacks are proliferating for a simple reason: Everything we do is increasingly digitized and stored online. The tools for such hacks—including step-by-step guides, malware, sample ransom notes and even 24-hour tech support—are easy to find in the dark corners of the web, and launching these attacks can be a way to make huge amounts of cash fast. According to the most recent StatsCan data, which included more than 9,000 businesses, 18 per cent of companies were impacted by a cyber-security incident in 2021. The attacks were designed to steal financial information, deface or destroy a company’s web presence or track business activity. Of those organizations, 11 per cent said they were subject to a ransomware attack, with nearly two in 10 reporting that they paid a ransom; some forked over more than $500,000. A small proportion of workplaces are spending large amounts of money on cybersecurity, but the majority spend little if anything. In 2021, the private sector spent $9.7 billion on cyber protection, up from $7 billion in 2019. “It’s a huge surge, a 40 per cent increase in spending,” says David Shipley, CEO of Beauceron Security in Fredericton. “And what was the end result of that? In 2021, we had $600 million in losses. That’s up from $400 million in 2019.”

Vachon-Desjardins has a shaved head and carefully sculpted pectorals, visible even through his shirt. He chose a pragmatic career trajectory, attending La Cité collégiale (now called Collège La Cité), a French-language college in Ottawa, for a degree in computer science. Upon graduation, he found work as a computer analyst at the University of Ottawa and then landed a government job. Most of his work involved providing technical support, helping other government workers who were having a bad day with their computer.

But Vachon-Desjardins showed early warning signs that he was not committed to the straight and narrow. In 2015, at the age of 27, he was charged with seven counts of possession for the purpose of trafficking cannabis, amphetamines, methamphetamines, cocaine, GHB and cannabis resin—some of which he had been trafficking since 2012. Vachon-Desjardins wasn’t just a drug dealer; he was a supplier to sellers and used his home as a central cache for large volumes of substances. When the police raided it, they found more than 45 kilograms of marijuana in a locked room along with over 60,000 methamphetamine tablets, 8,600 grams of hashish, more than 13,000 ecstasy pills, and a money-counting machine. Still, Vachon-Desjardins’s tastes appeared modest; at the time of his arrest, he was making $57,000 a year at his IT job and drove a Toyota Camry. Vachon-Desjardins’s girlfriend told police that he believed he would never face consequences for his actions. “He thought of himself as a god,” she said. After he was released from prison, having served only a fraction of his three-and-a-half-year sentence, he moved back in with his parents, who lived in a two-storey house in Gatineau. In October 2016, despite his criminal record, he secured a new government job when he was hired by Public Services and Procurement Canada.

He continued to live a double life, once again trafficking drugs—something he was busted for a second time in late 2019—while working in the public sector. The FBI believe it was a few months later, while working from home and awaiting drug charges, that he became active with NetWalker. There was clearly something that drew him to a lucrative underworld. And soon he would find a much more profitable black market to be a part of.

Anyone anywhere can be a cybercriminal, and there are few barriers to entry. Vachon-Desjardins was recruited by NetWalker in a strangely mundane way: He answered a classified ad on the dark web. It was posted by someone who used the name Bugatti, and the ad explained that NetWalker was looking for individuals willing to commit ransomware attacks—ideally Russian speakers (which Vachon-Desjardins was not) but mainly people with some technical knowledge and a willingness to skirt the law.

The conventional image of a computer hacker is some lonely nerd sitting in a dark basement, his oversized spectacles illuminated by the blue light emanating from at least two monitors. But ransomware attackers are actually a global network of highly organized criminals with a sophisticated franchise model composed of individual associates. NetWalker first appeared in 2019 and was made up of Russia-based developers as well as affiliates all over the world. The group gained traction during the pandemic by sending phishing emails with a link that, when clicked on, allowed them to exfiltrate and encrypt sensitive data that they would then hold for ransom. But they soon pivoted to a ransomware-as-a-service (“RaaS”) model, providing tools to approximately 100 affiliates in exchange for a commission on successful attacks. Those affiliates were charged with finding high-profile networks with security vulnerabilities; in return, they received perks like assistance with negotiations and access to frontline threat agents who offer technical support. Affiliates take a company’s information hostage—sometimes terabytes of data, which can include private health information, proprietary business files, diplomatic secrets—and the options for recovery are limited: Pay up or suffer the consequences. Over the course of NetWalker’s year-and-a-half criminal enterprise, the group extorted over 5,000 Bitcoins in ransoms, or more than US$40 million. One cybersecurity expert likened the difference between operating as a lone wolf and linking up with NetWalker as the difference between a no-name burger joint and McDonald’s: Who wouldn’t want to go with the brand name and have all the perks of a franchise model?

Vachon-Desjardins was ready to start his attacks by April 2020. The ransomware provided to him by NetWalker was a type of malicious software, or malware. He had access to a massive database of usernames and passwords—most of which came from open-source information online—that belonged to businesses and institutions and would try them one by one until he made a successful hack. Once he breached a company’s digital defences, he would encrypt its data, making it impossible for workers to gain access. Even if his victims could see their files, they couldn’t open them. Next, he would scan for sensitive data, like trade secrets, employees’ personal information, confidential patient or customer details or financials that a company would prefer to remain private—the stuff that makes an organization vulnerable to blackmail. Once he was done locking things down and surveying the materials he now held, he would send his ransom letter—a template from NetWalker that he’d adapted, injecting wording he felt might have a bigger emotional impact. Then he would ask the organization for a ransom of one per cent of its annual revenue, to be paid in Bitcoin through a public blockchain that records transactions but keeps identities confidential.

“It’s entirely inappropriate to pay the ransom simply because, on a strict basis, that may be the cheapest option for the business”

One by one, Vachon-Desjardins breached the private computer networks of different Canadian entities, including a software company, a travel insurer, a law firm, a CEGEP and a small, picturesque Quebec town on the bank of the St. Lawrence River. Ville de Montmagny, the self-described “white-goose capital,” had all its data encrypted and three servers shut down just as it was about to print tax slips. Vachon-Desjardins even targeted Collège La Cité, his alma mater. His victims appeared to have little in common, but there were a couple of things they shared: At least $30 million in annual revenue, the floor set by NetWalker for attacks, and certain security or software vulnerabilities that would allow Vachon-Desjardins to penetrate their systems.

When he was paid off swiftly and quietly, he held up his end of the bargain. But when a ransom wasn’t paid, he was also true to his word: He refused to decrypt the data and distributed the stolen materials on “the NetWalker Blog,” a dark-web website that existed for the sole purpose of punishing those who refused to pay ransoms. Depending on the information that was leaked, dark-web users might use it for the purpose of identity theft, further extortion or pure humiliation.

With his flexible moral compass and technological sophistication, Vachon-Desjardins was a natural. And he quickly developed a reputation among other hackers as someone who could attack and secure ransoms with relative ease, assuming a role as head misfit and even teaching dark-web classes about ransomware and malware deployment to aspiring cybercriminals. Some of those who approached him hoped to replicate his actions. Others wanted to learn how to secure their networks to ensure that someone like him could never hack their systems.

There’s no question that Vachon-Desjardins was interested in money—and being a ransomware affiliate offered him an extremely quick path to riches. Over the course of his criminal spree, he collected more than 2,000 Bitcoins and paid NetWalker hundreds of them. Flush with digital currency, Vachon-Desjardins managed to exchange almost $1.8 million in Bitcoin for cash. (The RCMP declined to comment on how he converted the Bitcoin.) But the amount he managed to extort was much, much higher. And yet, for someone who was obsessed with amassing money, he continued to live an understated life. He still drove a modest car—a Corolla—and lived in an unspectacular suburban home.

Cybercrime is a global problem, but countries have mixed approaches to addressing it and varying levels of success. The United States has taken a top down approach, including two White House presidential-level summits on ransomware (the most recent in fall 2022). Australia, which recently suffered a catastrophic attack on Medibank, one of the country’s largest private health insurers, has also beefed up its efforts. When Medibank didn’t pay the requested ransom, hackers released patient records related to abortion, addiction, mental-health issues and HIV/AIDS. In response, Australia named a federal minister for cybersecurity and formed a permanent joint task force between the Australian Federal Police and the Signals Directorate, which is part of the national security establishment. “Australia is mad as hell, and they’re not going to take it anymore,” says Shipley. “They’re going to burn the hackers’ tools, wreck their infrastructure and attack the economics of this crime.”

Global ransomware attacks increased by 151 per cent in the first half of 2021 compared to the first half of 2020

Canada’s National Cyber Security Action Plan was launched in 2019, and it consists of an array of measures, from the upgrading of critical security infrastructure to the fostering of relevant public-private partnerships. There’s a voluntary certification program to help small and medium businesses implement firewalls, training and software upgrades and even buy cyber insurance. But according to a 2021 report from the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, global ransomware attacks increased by 151 per cent in the first half of 2021 compared to the first half of 2020, with half of the victims belonging to critical infrastructure, including health, energy and manufacturing. Most companies, large and small, invest in some form of virtual security, unaware that vulnerabilities remain. They might have software updates they haven’t pushed or neglected to train staff on even the most basic principles, such as never clicking on a link in an email unless you’re certain the sender is secure.

Hackers might pick targets they’re familiar with or pick them based on some perceived vulnerability. But Shipley says they’re also inclined to select organizations they believe are most likely to pay a ransom without a fuss. “Once they see a pattern of people paying, they start to understand it from a business perspective—the market segments, the buyer personas,” he says. “It’s very similar to any other business sales and marketing approach.” Paying a ransom might be seen as the cheapest and easiest way to make a hacker go away, but it creates all kinds of downstream problems—in particular, it incentivizes future ransomware attacks.

Shipley says he was working in IT security at the University of New Brunswick when a Western Canada university paid a $20,000 ransom. Almost overnight, UNB saw an increase in malicious emails with attachments, from 120,000 a month to 1.2 million. Shipley believes that insurance companies, which offer policies that cover damages from ransomware attacks, have exacerbated the problem and that the payment of ransoms should be prohibited by provincial regulators. Instead, they should offer insurance products that cover cyber recovery and rebuilding post-attack. “It’s entirely inappropriate to pay the ransom simply because, on a strict basis, that may be the cheapest option for the business,” says Shipley. “It’s that classic tyranny of the commons: What’s good for me as an individual can be bad for society.”

Cypfer, a Toronto-based company with global offices that coordinates responses to ransomware attacks, is often on the receiving end of panicked phone calls from businesses, which sometimes arrive in the middle of the night. Ed Dubrovsky, COO and managing partner, leads a team accustomed to working during the crisis phase. Their job is to first assess exactly what has happened and then negotiate a recovery strategy. Cypfer takes over communications with the attackers on behalf of the hacked business. On occasion, Dubrovsky says he’s been able to push bad actors to return data with an apology—usually through some combination of guilt and threat of legal action. Some hackers simply want to do damage, so it’s a question of figuring out how to minimize it by kicking them out of the system, focusing on recovery and ensuring they can never break in again. But about 40 per cent of the time, money does change hands. The question is how much: How much is the information worth, how much can the company afford to pay and how much will it take to convince the attackers to retreat?

“Once they see a pattern of people paying, they start to understand it from a business perspective—the market segments, the buyer personas”

In his seven years of taking on hackers, Dubrovsky says, he’s worked on close to 5,000 cases—and every one was different. But each interaction, typically over an instant messaging platform or burner phone, has an element of theatre. “Every time we start a negotiation, I take on a persona,” says Dubrovsky. “Obviously, I don’t come out and say ‘Hey, this is Ed speaking to you, and by the way, I live on this street, and let’s go for coffee.’” Instead, behind the anonymity of online interactions, Dubrovsky can play multiple characters—perhaps someone who’s quite aggressive and gets fired up, and then a new, more reasonable negotiator enters the scene. It’s techno good cop, bad cop.

Attackers hide behind anonymity and share the same refrain: This is just business. But there’s a real person behind the computer monitor—and Dubrovsky sometimes tries to tap into their empathy. He listens for cues of a guilty conscience; the hacker might express concern for his victims, for example, noting that he really doesn’t want to damage their business. “If they start a conversation like that, then I will definitely try to start the violin music in the background,” he says. He tries to convince them to go easy, that this is a small business or a hospital that’s just trying to help people get through their day or one of the worst moments of their life. On occasion, the tactic works and Dubrovsky can secure a promise not to publish any stolen data. Multiple times, he’s convinced a hacker to sign an NDA. Jason Kotler, Cypfer’s president, says that they have been successful in convincing hackers not to attack similar victims by making a case for the industry’s social significance during a global pandemic. “They were ancillary health and support services, and the hackers said, ‘You know what, going forward, we get your point,’” says Kotler. “‘This victim will pay, but we’ll change our rules and no longer attack similar organizations.’”

Still, even if the negotiation is successful, a ransom might be paid. Dubrovsky ballparks the average payment at around US$800,000, though he’s seen demands as low as US$50,000 and as high as US$180 million. “Sometimes the numbers don’t make sense,” he says. “The hackers make mistakes. They might think they’re attacking a big company when it’s actually a very small company, or the impact is actually very low. It’s all on the negotiator to bring them the reality of the situation.”

On May 1, 2020, several computers at a business in Tampa, Fla., suddenly flashed a note: “Hi! Your files are encrypted by NetWalker… If for some reason you read this text before the encryption ended, this can be understood by the fact that the computer slows down and your heart rate has increased due to the ability to turn it off, then we recommend that you move away from the computer and accept that you have been compromised.”

The message included a unique code and URL for a site, NetWalker Tor Panel, hosted on the dark web. When an employee at the Tampa business used the code to log on, they were presented with the ransom amount: US$300,000 in Bitcoin. They decided not to pay. But efforts to respond to the attack—containing damage and restoring operations—ultimately cost the company US$1.2 million.

The FBI was alerted, and in the course of their investigation, they seized copies of a backend server used by NetWalker. On that server, they found detailed information about the group, including both developers and affiliates. Soon, the FBI had narrowed in on their target, a Canadian national. In August 2020, the RCMP was alerted by the FBI that a NetWalker affiliate was operating in Gatineau and that the individual was responsible for ransomware attacks in Canada and the U.S. The FBI disclosed that the attacker had raised more than US$15 million through ransom payments. And they had a name: Sébastien Vachon-Desjardins.

The RCMP investigation was led by Craig Elliott, a middle-aged officer with a narrow face, a shiny bald pate and an earnest demeanour. Elliott’s investigation was being run in tandem with the FBI’s, which gave him the sense that there was a ticking clock. They were informed that an extradition warrant was coming as early as January 2021, so they would have to act fast if they wanted to interview and prosecute Vachon-Desjardins before the Americans got to him. It was the height of the pandemic, and there was a lot of uncertainty with a newly remote RCMP workforce. And now they had a limited period of time to collect as much information as possible. It quickly became an all-hands-on-deck, is-there-any-coffee-left case as they set to work on investigating Vachon-Desjardins, examining IP addresses, email addresses, aliases, social-media platforms and information supplied by Apple, Google and Microsoft. A key challenge was triangulating the information they discovered as they waded deeper and deeper into Vachon-Desjardins’s online life with the very real victims of his attacks—most of whom were not known to authorities.

“I think some of it was curiosity to see how well he could do. And he did very well.”

Alarm bells started ringing for Elliott when he did some preliminary background research and discovered Vachon-Desjardins’s day job: He was employed as an IT worker for the federal government. Investigators didn’t want to tip off Vachon-Desjardins while they were still sneaking around his crime scenes, so the RCMP shared information with his employer, and he was reassigned to a unit where he would have limited access to sensitive materials while the police worked their case.

At the same time, law-enforcement agents in the U.S. targeted NetWalker infrastructure, identifying and seizing copies of a server that supported their attacks—including those carried out by Vachon-Desjardins—and provided a platform on which to release sensitive hacked data or information. When they examined the server, they discovered details about affiliates and developers—and the vast scale of their unlawful activities.

For someone so tech-savvy, Vachon-Desjardins left a lot of fingerprints. Investigators found evidence of his research into the hacked networks as well as the tools he used to both steal and encrypt company data. Accounts linked to Vachon-Desjardins posted stolen victim data on the NetWalker blog. The ransoms he collected could be tracked on a Tor site (which anonymizes online interactions) accessible to both NetWalker and its affiliates. Crucially, they were able to link a moniker he used in his extortion, User ID 128, to a server in Poland—where he left behind an IP address. And the investigation also confirmed something else: Vachon-Desjardins had indeed been a star pirate. He successfully extorted US$21.5 million from dozens of companies around the world—more than half of the US$40 million extorted by NetWalker affiliates worldwide.

At the end of January 2021, the RCMP executed a search warrant at Vachon-Desjardins’s Gatineau home and gained access to his bank accounts, including safe-deposit boxes at National Bank. They confiscated over 30 devices, which contained a total of 20 terabytes of information. If this data were printed, according to court documents, it would fill an entire hockey arena—a distinctly Canadian unit of measurement. Police also found a huge amount of cash in his home—$640,040—and another $420,940 in his bank accounts. Pictures distributed by the RCMP show piles of stacked $20, $50 and $100 bills as well as a six-monitor, two-keyboard desk set-up. In the end, the RCMP seized 719 Bitcoins from Vachon-Desjardins’s e-wallet. At the time they were seized, they were worth about $28 million. Almost immediately after Vachon-Desjardins was arrested, he decided to co-operate with Canadian authorities.

In a November 2021 video shared by the RCMP, Vachon-Desjardins sits at a table with his hands clasped in front of him. He is calm and polite, wearing partially frameless glasses and speaking English with a discernible Quebecois accent. He could have been answering questions at a job interview. He seems, if not quite apologetic, eager to share his knowledge. Francois Picard-Blais, another RCMP officer involved in the investigation, describes him as the kind of person you would like to have a beer with. “He’s a very intelligent guy,” he says. “I think some of it was curiosity to see how well he could do. And he did very well.”

In January 2022, shortly after he pleaded guilty to those drug-trafficking charges in Quebec, Vachon-Desjardins pleaded guilty to his complex scheme of mischief: theft of computer data, extortion, the demand of cryptocurrency ransoms and participating in the activities of a criminal organization. During a virtual hearing, he apologized profusely for the harm he had done. But if he hadn’t been caught when he was, it appears that Vachon-Desjardins was intent on continuing down his illicit virtual path. Just before the search of his home, Vachon-Desjardins had transferred 224 Bitcoins out of his e-wallet. It was a payment to NetWalker for the latest malicious code for use in future ransomware attacks.

In a written judgment, Justice G. P. Renwick described Vachon-Desjardins in uniquely glowing terms. “The Defendant was pleasant and respectful in court,” he wrote. “He is good-looking, presentable and instantly likeable.” It never hurts to be considered attractive by one’s presiding jurist, but perhaps it was actually the intoxicating air of mystery that the judge was so taken with. Through the proceedings, Vachon-Desjardins remained a cipher. Unlike so many criminal defendants eager to round out their character with glowing references, Vachon-Desjardins provided none. There was nothing that might explain or mitigate his motivation. There were no letters from friends or family explaining that he was otherwise loving and conscientious; no counselling reports zeroing in on early-life trauma or a previously undiagnosed personality disorder. Vachon-Desjardins didn’t find religion or explain to the court that he was eager to serve his time and return to gainful employment. He was content to remain a black box—someone who was caught but not known.

In the end, the RCMP seized 719 Bitcoins from Vachon-Desjardins’s e-wallet

A total of 17 Canadian victims suffered more than $3 million in losses. In his written decision, Justice Renwick noted that sentencing parity would be extremely difficult in this case, given that it’s the first of its kind in Canada. “The Defendant is not a first-offender,” he wrote. “He is a sophisticated cyber terrorist who preyed in an organized way with others on entities in educational, health-care, governmental and commercial sectors. His crimes are extreme and significant.” He ultimately sentenced Vachon-Desjardins to seven years in prison and ordered him to pay almost $3 million in restitution.

His conviction in Canada was not the end of his legal troubles. In March 2022, Vachon-Desjardins was extradited to the United States, where he again pleaded guilty in a Florida court and was sentenced to 20 years in prison. It’s clear that he operated as a member of a criminal network, but no co-conspirators have been charged, and the RCMP declined to comment on this. In any event, NetWalker disbanded after the FBI seized a server in Bulgaria that it used to coordinate RaaS attacks.

Vachon-Desjardins is presently incarcerated at FCI Fort Dix, a low-security federal institution in New Jersey. (When contacted for comment, Vachon-Desjardins’s U.S. attorney said his client does not wish to speak to media.) Shipley says Vachon-Desjardins got caught because he was overconfident and greedy. “If he had been smart and hadn’t gotten cocky… Once you make $20 million, you should realize, ‘Okay, it’s time for me to get out of Canada and just disappear.’”

Vachon-Desjardins has a projected release date of 2039; he’ll be in his 50s and promptly returned to Canada. It’s anyone’s guess what additional skills he will pick up in prison and whether his time behind bars will inspire him to go straight or—as was the case when he served time for drug trafficking—embolden him further. Pleasant looking, co-operative and deviously smart, he’ll have had plenty of time to ruminate on his own actions and exactly what he was trying to prove—and if there could ever be enough money to make him walk away from his keyboard.

This article appears in print in the Spring 2023 issue of Canadian Business magazine. Buy the issue for $7.99 or better yet, subscribe to the quarterly print magazine for just $40 a year.