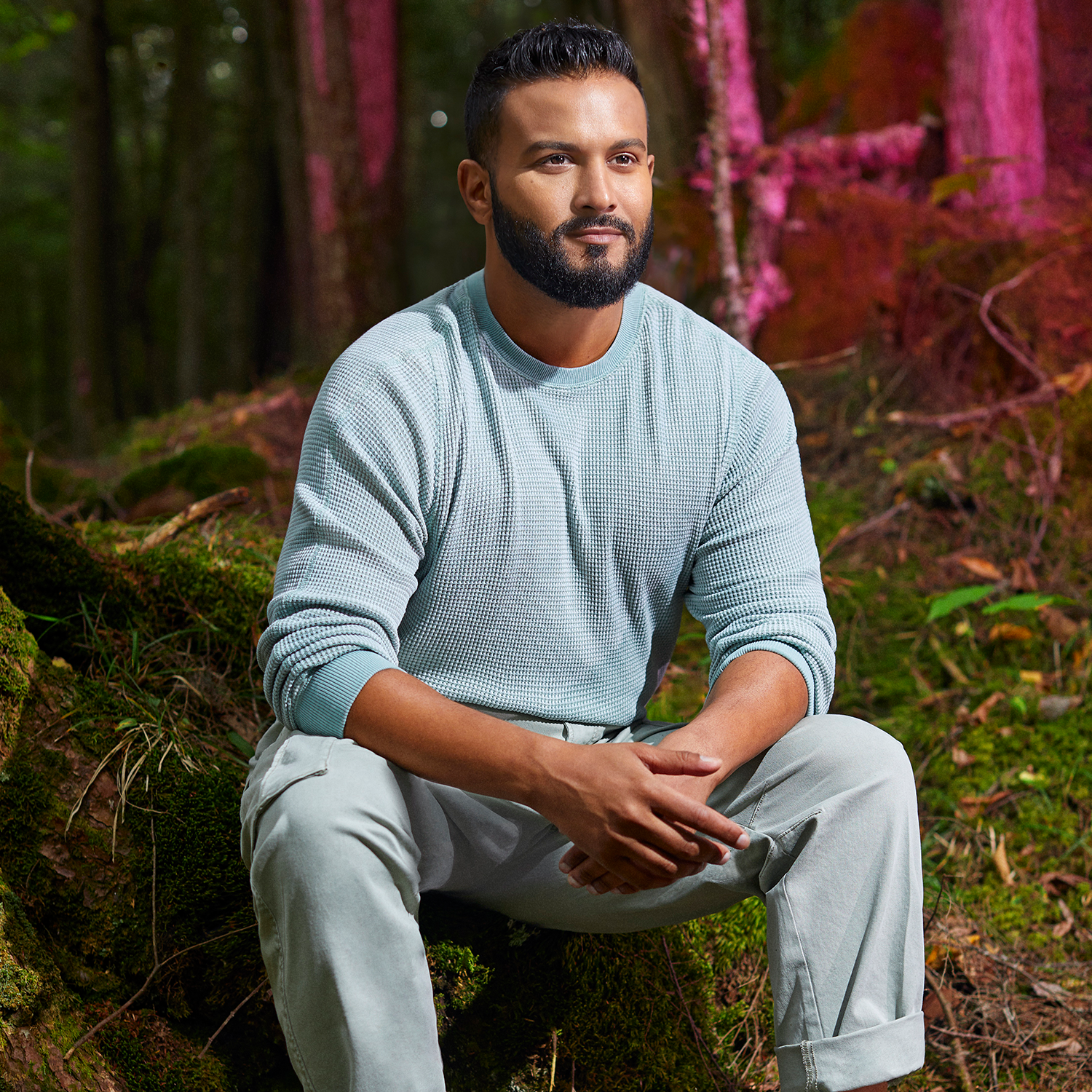

‘I Had to Park My Ego’: How Spin Master Co-Founder Anton Rabie Built a Multi-Billion-Dollar Toy Business

Anton Rabie started his toy business, Spin Master, fresh out of university with his friends Ronnen Harary and Ben Varadi. The company grew from a single product to a global toy and entertainment company known for some of the most popular children’s brands on the market, including Air Hogs and PAW Patrol.

I grew up in Cape Town, South Africa before moving to Toronto at the age of six. I was raised in a very loving but competitive household. As the middle of three brothers, sports played a big role in my life. From the ages of eight to 11, I played hockey, wanting to move up to rep level. But I was skinny and hit puberty late.

In school, I was often kicked out of class for being easily distracted. I used to write exams in separate rooms because I processed information differently. My folks couldn’t afford to seek a diagnosis about a potential learning disability, so we didn’t know what it was. (To this day, I still don’t.) These early struggles created an even deeper, more conscious, competitive streak in me. I needed an outlet to prove myself.

My first jobs were shoveling driveways and working a paper route at the age of nine. The Saturday stack of the Toronto Star was heavy, but it didn’t stop me from completing my deliveries. I carried this determination with me into my teenage years. At 17, my friend Ronnen Harary (who later became one of my Spin Master co-founders) and I sold fertilizer to thousands of homes in Thornhill, Markham and London. Ronnen and I would use his VW Westfalia to make deliveries. By the end of a long, grueling day, we’d hear the word “no” so many times. Ronnen would say, “I’ve had enough.” But I’d keep going, which surprised him. “I’ve never seen anyone who takes rejection so effortlessly,” he’d say.

I went to the University of Western Ontario for social psychology. During the summer months, Ronnen and I would sell posters to students, which led to us eventually starting a business together. In 1994, fresh out of Western, we put our savings and $10,000 each on our credit cards towards launching a toy product called Earth Buddy while working from Ronnen’s basement. Earth Buddy was a nylon-covered head of sawdust topped with grass seeds which grew to look like hair. We did the market research and believed it would sell. It turned out to be a hit: Kmart ordered half a million units, equalling over $2 million in sales.

At that time, all we were thinking about was Earth Buddy and how to maximize that one item. There wasn’t some grand plan for a worldwide powerhouse of a company. It was about taking advantage of that product, riding the wave. We were a couple of pipsqueaks from university. But thanks to our determination and a lot of early press, we made a big splash and started our business.

Through a friend of a friend, we managed to rent an office space in Toronto. We didn’t have a lot of answers as to how to run a company. Instead, I’d ask questions relentlessly. At the New York toy fair, I’d ask reps questions like, “How’d you figure out pricing?” and “How’d you go from $4.99 to $5.99?” I’d ask retailers, “How do you manage sales channels?” I was learning everything I could about the toy business. We began marketing Devil Sticks—batons used for in-air tricks—in 1995 by sending college students across the country to demo the product on campus. By the end of the year we sold 600,000 units.

In my late 20s, I went to Hong Kong to meet buyers for Toys “R” Us and Walmart. To show how we were filling a need in the marketplace, I wanted to get face time. Between 6 p.m. and 8 p.m, I’d hang outside the building where buyers would meet, knowing they’d be picked up for dinner there. A lot of them didn’t know me, but I was determined to talk to them. And I did.

Ronnen and our other co-founder, Ben Varadi, who joined the company in 1994, had clear roles at Spin Master: I handled the people-facing work, like sales, which blended well with Ronnen and Benny’s product innovation knowledge. They focused on creating new toys that redefined the industry—what I call “category busters”—like Air Hogs, a line of air-powered planes we launched in the late 1990s. Like in a rock band, we each played a different instrument. This was a key to our success.

Even as the business grew to $10 million by 1998 and $2 billion in 2021, I was obsessed with continuous improvement. From Ronnen and Benny, I’d often hear, “It’s exhausting being your partner,” because nothing was good enough for me.

Still, we’ve had our share of adversity. I had to park my ego. In the early years, the results of my first review as co-CEO were painful (Ronnen and I shared the top job). I scored a 5.8 out of 10 on listening. I remember thinking: ‘If I don’t improve, I’ll no longer be the person to run this company.’ I worked with multiple life, career and business coaches. It was a decisive moment, something I had to—and did—overcome.

We’ve also had downturns. In 2010, we suffered a setback. It was caused by several factors including a shaky economy. Sales volume decreased from $900 million to $470 million on our Bakugan line of toys and entertainment, which represented 40 to 50 per cent of our revenue. We put our heads down and rolled up our sleeves. We had to let go of people, tighten costs and relook at our shipping and forecasting plans. It was an eye-opening time. I was learning things like how to manage downturns, how to better understand the natural life cycle of a product and how to build a more robust brand. Even today, outside my office on King Street in Toronto, I’ve pinned a list of personal failures on the wall as a reminder of things I still need to improve on.

Strategically, Spin Master has three creative centers: toys, digital and entertainment. What I’m most grateful for is that we’re now in the best position ever. Employee engagement, cash on hand, diversification—they’re all healthy. We also recently acquired the licensing for the Rubik’s Cube.

Above all, Spin Master’s north star is legacy. Since handing off CEO duties to Max Rangel a year ago (who entered into the role from another organization), my focus now is to help others achieve greatness through mentorship. I have an open-door policy. I help employees form answers to questions such as: How do you become less risk-averse? How do you become the best leader? How do you work through your fears? I’m fully engaged in promoting excellence and advancement.

Success through leadership is truly about mindset—the mental, emotional and strategic qualities you need to cultivate in the midst of any challenge. I started out small. But I learned that, inside the small thing, the big things are waiting.