When the wildfires came through B.C. this summer, they moved like lightning. At the height of the crisis, more than 40 fires burned, covering one million hectares of land. In some cases, the devastation was instant. On June 30, the town of Lytton, at the nexus of the Fraser and Thompson rivers, hit a record temperature of 49˚C. Within 20 minutes of the mayor’s evacuation notice, it had been engulfed in flames. More than 90 per cent of the town was destroyed, two people died and more than 1,000 residents were displaced. The damage in Lytton alone is estimated at $78 million, and the priority now is to make the area habitable again—and to replace its trees.

Reforestation is a vital and time-sensitive part of wildfire recovery. Without trees, the soil will eventually erode, threatening habitats and ecosystems. Now that climate change has made wildfires a given in western Canadian summers, trees are in constant danger. It’s time to fight fire with…drones?

That’s where Flash Forest comes in. The start-up, based in suburban Toronto, is the first reforestation company on the Canadian market that uses unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, to plant trees. Flash Forest has run some of its most successful pilots in the pliable, eager soil of fire-ravaged sites using a proprietary combination of automation, aerial-mapping software and meticulously engineered seed pods that regenerate ecosystems—and fast. The UAVs can plant far more efficiently than people can, moving quickly to seed burnt forests before the undergrowth returns. By bringing drones to what has historically been a bag, shovel and itty-bitty-seedling fight, the Flash Forest crew hopes to plant one billion trees by 2028—a goal that’s ambitious and optimistic, yes, but imperative.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, we need to limit atmospheric temperature increases to 1.5˚C in the next decade or risk facing environmental catastrophe. One way to do that is to increase our collective forest cover by 1 billion hectares. To do its part for the planet, Flash Forest will have to scale up its business as quickly as it formed. The acid test of its mandate is preventing the planet’s sixth mass extinction. No pressure.

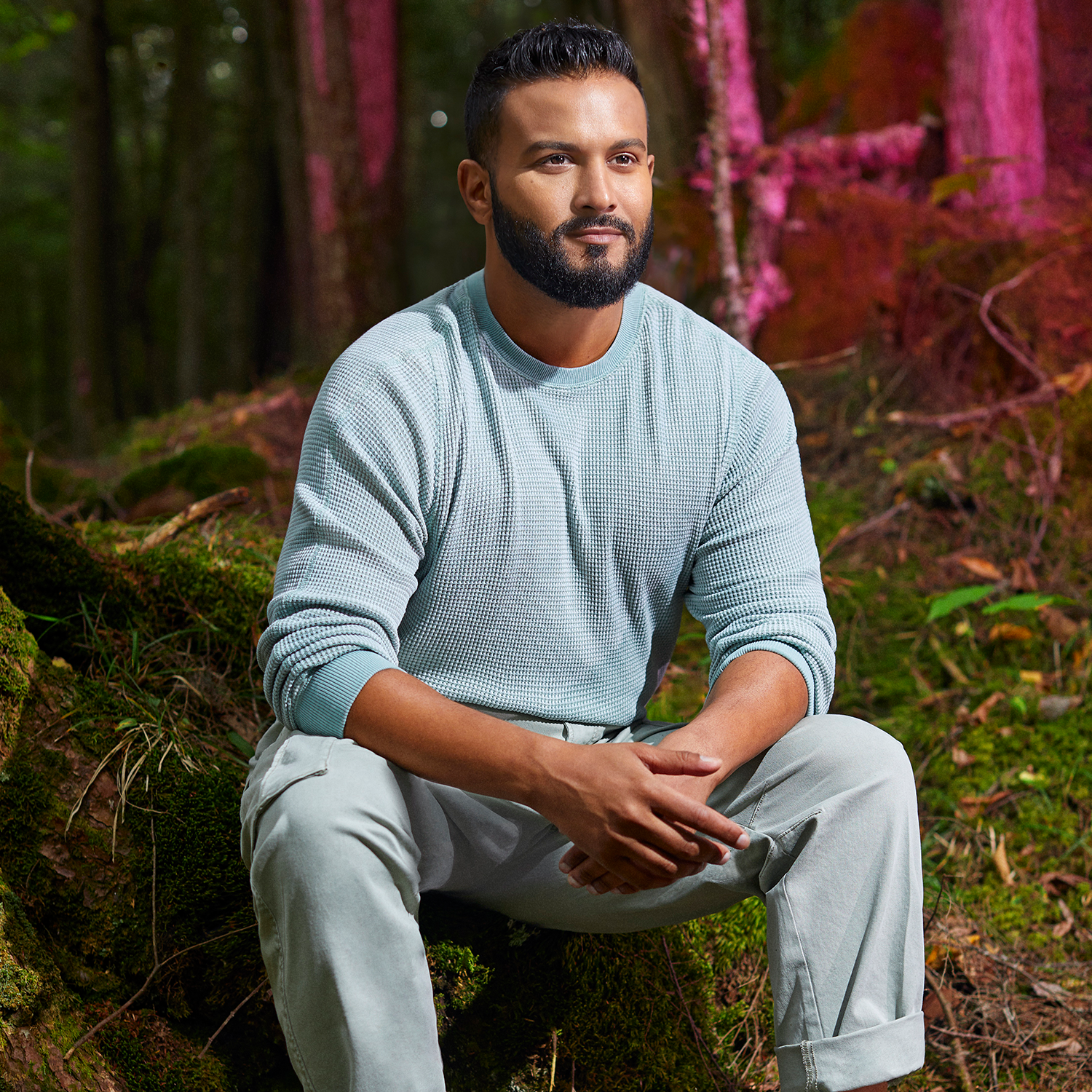

Flash Forest’s CEO, Bryce Jones, speaks with the relaxed cadence of someone who works outdoors, but it’s clear he thinks in moonshots. Jones currently lives in southern Ontario, but at heart he’s a west-coast kid who has fond memories of surfing off Vancouver Island and spending time at the lake in the Okanagan Valley. When it comes time to describe himself, though, he uses words like “curious” and “entrepreneurial” rather than “outdoorsy.”

Jones studied engineering, worked as a solar energy consultant and spent time tree planting. He initially passed on a few other environmental start-up ideas before deciding to develop a proof of concept in the spring of 2019 for what would eventually become Flash Forest’s bread-and-butter tech. The idea had few technological hurdles—drones are relatively affordable. They’d become increasingly sophisticated over the past decade and mainstream enough that people wouldn’t write them off as experimental. And they could potentially address the challenge at hand: When trying to outpace the effects of climate change, you need to act fast.

By the summer of 2019, Jones had teamed up with his older brother, Cameron—once a frustrated climate-policy worker with the Government of Alberta, now the chief operating officer at Flash Forest—as well as Angelique Ahlström, a former tree planter who previously worked as COO for a Canadian tech-ed firm. Ahlström is Flash Forest’s chief strategy officer. She met Bryce when the two attended the University of Victoria. The fourth founder of the company is Andrew Lauder, an experienced product designer and Shopify veteran who’s worked with the Jones brothers on ventures in the past.

The Flash Forest team’s first drone test flight took place in the backyard of one of Lauder’s relatives. The prototype was fairly makeshift: It was an M600 drone that Bryce had modified with a pneumatic deployment device and packed with rudimentary seed pods. The pods contained a mix of off-the-shelf ingredients and garden-variety soil mix. They were cast using a 3-D printer that belonged to his engineering school. Its flight was amazing validation, says Bryce. As a former tree planter, he was well aware of Canada’s diverse and perilous topography, vast tracts of which can only be accessed by air.

Further validation came in early 2020 when the partners launched a Kickstarter campaign. More than 1,600 backers raised $108,713 to support Flash Forest’s automated environmental idealism, smashing the team’s initial $10,000 goal. Soon after, the four founders gained a fifth team member in Greg Crossley, an engineer. The project caught the attention of news media. A small army of intrigued venture capitalists, non-profit forestry folks, and climate academics came on board. Before long, Flash Forest had an adviser in John Innes, the dean of forestry at the University of British Columbia and a key player on the IPCC team that shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore.

Early friends-and-family and equity-funding rounds raised $400,000 and $1 million respectively. The start-up also received grants totaling $3.5 million, including one worth $1.8 million from Emissions Reduction Alberta.

This bottle-rocket combo of good PR and funding paved the way for Flash Forest’s upgrade from backyard target practice to a proper headquarters in Brampton, Ont., and a 17-person org chart that’s stacked with specialists in business development, engineering, geomatics, mechatronics and plant science. “Many of them came to us,” says Bryce.

Flash Forest isn’t the only drone-reforestation company in the game; there are Dendra Systems based in Oxford, England, and Seattle’s DroneSeed, to name just two others. The advantage that Flash Forest has on its competitors is speed and seeds.

A single operator can control a fleet of drones that can fire off hundreds of spherical wonder pods in a matter of minutes. The company’s pods—developed by a team of botanical specialists—contain tree seeds, nutrients and helpful fungi known as mycorrhiza, all of which help seedlings settle into their eventual drop sites and survive months in the field.

Tyler Hamilton, a director specializing in cleantech at Toronto’s MaRS Discovery District, has followed Flash Forest’s rise. He refers to the pods as the company’s “Cadbury secret.” This spring, Flash Forest was recognized as one of 10 “champions” of the Mission from MaRS: Climate Impact Challenge, which assesses the potential of Canadian start-ups to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in carbon-heavy industries such as transportation and energy. MaRS connects winners to advisers and funding sources. Hamilton and his team of judges were particularly impressed by the way Flash Forest “nailed the seed science,” which Cameron says is where the team is focusing its IP development.

The start-up’s founders estimate that they’re on track to manufacture hundreds of thousands of pods a day at their Brampton warehouse over the next year. “They’re not like some dried pellets that just sit there on the surface and don’t take root,” says Hamilton. “Because of the design, these guys dissolve upon exposure to moisture, so they’re off to a good start once they hit the ground.”

The team’s goal, Bryce says, is to promote “biodiversity over monocultures,” respecting every site’s natural topographic smorgasbord. Flash Forest has tested its technology across the country, as far west as the rainforests of Vancouver Island and as far east as southern Ontario. The team has consulted local nurseries, governmental and forestry agencies, and First Nations leaders. Occasionally, they’ve travelled to lower latitudes, sourcing seed varieties that aren’t native to their planting areas but are robust carbon-suckers and stand a better chance of weathering the warming mutations of climate change.

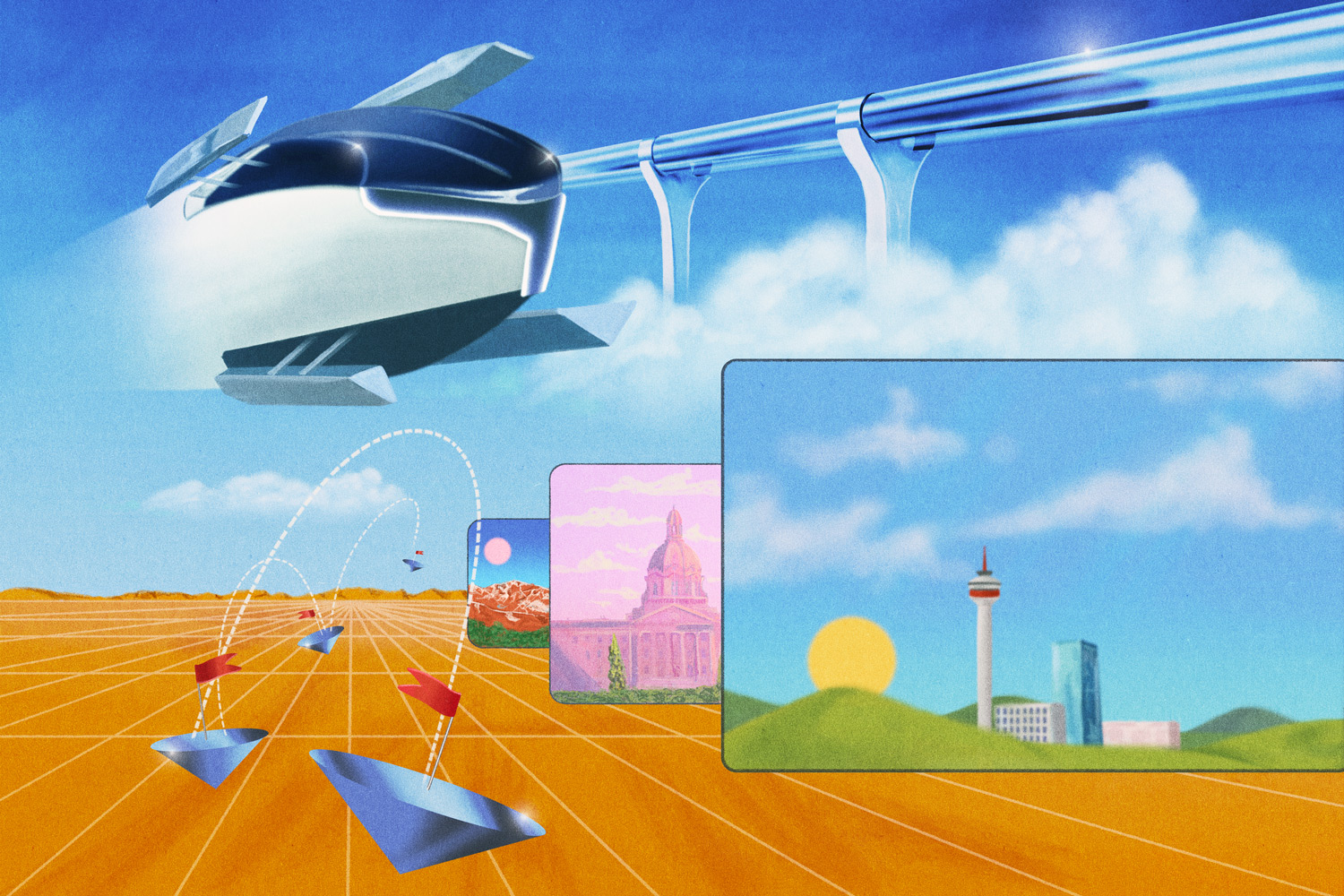

As for how the seeds get into the wild, that’s where Flash Forest’s suite of drones comes in. Once a pilot location is confirmed, a mapping drone is sent to survey the land. It creates a flight path that avoids unplantable spaces like lakes and roads. Once it lands, the drone can share its plotting data with the rest of the fleet. One operator can oversee five drones simultaneously, which is a direct threat to the quick-harvesting techniques practiced by the timber industry. Flash Forest’s drones can fly as low as three meters above a clear patch of land. They can launch pods from any height at a rate of one pod per second—and tens of thousands per day. The company’s target is to plant at 10 times the rate of your average human tree planter. Bryce says his team is very close to hitting that mark.

“We recognize first-hand the inherent challenges with manual tree planting: high injury and turnover rates,” says Ahlström. “Also, nurseries are super energy-intensive.” The founders didn’t really want to go in and directly challenge the tree-planting status quo. But forestry companies are reaching out to them, citing a shortfall of workers. “We see ourselves as helping their efforts with advanced tech,” she says.

Becoming successful in Canada is crucial for Flash Forest. If they can make drones work here, the founders can pave a path to the global adaptation of their technology. They’ve pulled off pilots in diverse ecosystems already but the team is zoning in on reforesting the boreal biome, which wraps the earth’s northern hemisphere in something of a woodsy crown.

Boreal forests contain 703 gigatons of carbon annually, compared to the 375 gigatons held by their tropical counterparts. “If we can master that, not only will we have access to forests in Russia, Scandinavia and Canada, we’ll make a very strong ecological footprint,” says Cameron.

Cracking Canada, however, comes with a good amount of political and commercial slowdowns, many of which the MaRS climate-tech springboard was specifically designed to surmount. The Flash Forest team has cast a wide net for partners: They want to work with NGOs, forestry companies, universities and corporate sponsors keen to meet the reforestation pledges in their corporate social responsibility mandates. Canada’s government agencies—saddled with urgent greenhouse gas targets, tree-planting labour shortages and limited nursery space for seedlings—are also obvious prospects.

Flash Forest has its one-billion-tree mandate, but the federal government’s goal is double that by 2030. The Two Billion Trees program is one part of a climate-friendly election promise from the Liberals, who budgeted $3.16 billion to expand Canada’s urban and rural forest cover by 1.1 million hectares over the next decade. That’s roughly the size of Prince Edward Island.

But the program is already riddled with snags. The government allocated funding specifically to traditional burlap-sack-and-seedling operations. The pandemic slowed the program’s initial rollout. Conservative environment critic Dan Albas even accused Trudeau’s cabinet of having “no plan.”

The scourge of red tape is all too familiar for Cameron. He decided to jump ship on his policy manager gig with Alberta’s Department of Energy and join Flash Forest after the UCP government scrapped four years’ worth of work on a comprehensive renewable-energy credit program in 2019—legislation that would have placed a consumer carbon tax on fossil-fuel products.

Initially, Cameron felt like the best way to influence change would be from a policy angle. “But the higher you get, the more you realize your scope of influence is not that great,” he says. The team believes that if they can make Flash Forest a profitable business for the public good, it will succeed long term, no matter the government in power. “And what the climate requires is a radical change, 100 per cent,” says Cameron.

Canada doesn’t want for climate solutions, but there is a widespread reticence to commercialize them. “If corporations and governments really get serious about climate change, as they need to do, then demand and investment will shift dramatically,” says Barnabe Geis, executive director of climate ventures for the Centre for Social Innovation and lead on the organization’s Earth Tech accelerator. (Flash Forest was a participant in 2020.)

“If our response is more like a wartime mobilization, we are going to create many more jobs and we’ll see one of the greatest economic opportunities of the century,” says Geis. “The flip side of that is economic and environmental ruin, and that’s not hyperbole.”

Tyler Hamilton of MaRS echoes Geis’s sentiments, pointing to a phenomenon called “pilot purgatory.” That’s when start-ups launch projects that languish before getting the chance at super-sized commercial traction, which can turn the ventures into an international success.

“It’s almost like we have this mentality where we plan for failure,” he says, noting that the vast majority of revenue-generating activities by small to medium clean-tech enterprises are done outside of Canada. “If we’re not adopting this innovation at home, it will be harder to sell globally, because the first thing start-ups are asked is, ‘Do you have examples of your technology being used in your domestic market?’” Canada loses out when its best climate-tech start-ups leave the country altogether. That can happen if regulators aren’t friendly or it’s taking too long for policymakers to keep up with the times, says Hamilton.

There’s no question Flash Forest has designs on global expansion, wherever its technology is needed. “And with people who understand that this is not a game,” says Ahlström. The team has a government contract secured for Hawaii’s big island in the winter. They plan to travel to the Netherlands early next year perform pilots and prove their pod technology in Europe. The European Union recently drafted a plan to expand its carbon sinks. Flash Forest is also targeting Brazil, Borneo, New Zealand and Australia, not just because they’re teeming with wildfires but also for the opportunity to restore the homes and food supply of the resident endangered species.

“If our response is more like a wartime mobilization, we are going to create many more jobs, and we’ll see one of the greatest economic opportunities of the century”

New markets will demand agility, but that’s something of a Flash Forest specialty—the company is very used to pivoting constantly. It relies on 3-D printers to cast its seed pods. COVID forced the closure of 3-D print shops, which could have easily tanked Flash Forest’s spring pilots in B.C., so the crew quickly turned to the Centre for Social Innovation, which opened up its tool library so their engineer could test parts. The Joneses say that they’ve also switched to entirely different deployment mechanisms while in the field; their old systems were just too time-consuming.

That maverick sensibility is, in part, an age thing. The majority of Flash Forest’s staffers are under 30. They wield the optimism and motivation of former tree planters and fresh university graduates. “They’re not just interested in the technology for technology’s sake, which often happens with start-ups,” Ahlström says. In fact, most of the staff were already climate stewards in their own right prior to being hired at the company.

“Young people want to make an impact in a way that traditional academia and big companies sometimes don’t offer,” she says. “It’s a great thing to go to sleep at night knowing that everyone is giving their all.”

Despite what conventional marketing will tell you, it’s rare that a company’s output is inextricably tied to the survival of the human race. Flash Forest is the exception. Bryce Jones says that between the smoke-shot skies, biblical floods and mussels cooking open in place on beaches in B.C. and California, the team regularly gets visceral reminders of the urgency of getting things right. At the same time, they know that mitigating climate change is an all-hands-on-deck effort.

“This is definitely not something we can do on our own,” he says. Meat substitutes and low-emission air conditioning are his kind of start-up ideas for how to curb the 51 billion tons of greenhouse gases we produce annually.

But trees are our oldest and best lifeline. Next year, Flash Forest’s team will hold planting trials for more than 20 species, including white and red pine, coastal Douglas fir, western hemlock, and hybrid spruce. They’ll also be workshopping ways to ensure their seedlings reach the size and strength necessary to pull through unmerciful winters. Whatever the circumstances, they’re focused on one thing: growth.